From the Beach Boys to the Beatles, from the Stones to the Ramones, here are the 25 greatest rock bands of all time. If you’re new here, be sure to check out the series introduction where I lay out what qualifies a band for inclusion on this list (be a band; be excellent; be successful; or be influential!). I also describe my unavoidably personal ranking methodology and explain why I include rap, soul, and vocal groups in a list of “rock bands.”

If you already know the rules, you can jump right down to the list.

See Who Else Makes the List

- The 100 Best Rock Bands of All Time: 50-26

- The 100 Best Rock Bands of All Time: 75-51

- The 100 Best Rock Bands of All Time: 100-76

What is Rock?

Simply stated, Rock Music formed the basic DNA of popular music from about 1960 to 2000.

The 1950s are fondly remembered as The Golden Age of Rock and Roll. Much of what we would call Rock and Roll—Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, etc.—is firmly rooted in the blues, gospel, country, and R&B which came before it. But when these sounds merged—and most importantly, when the line separating Black and white music blurred—the cultural phenomenon known as rock and roll engulfed America’s youth.

Then, in 1959, a series of unfortunate events signaled an end to this era, including Elvis Presley’s draft into military service, Little Richard’s departure into the priesthood, and the tragic airplane crash that claimed the lives of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper.

Rock and Roll had reached its first low ebb, leaving popular music in the well-manicured hands of treacly teen idols like Frankie Avalon and Fabian. Rock and Roll had many critics, including an outspoken contingent of segregationists who decried the spread of so-called “jungle music.” Those who thought of rock and roll as coarse, vulgar, and little more than a teen-fueled fad were vindicated. Rock and roll was dead.

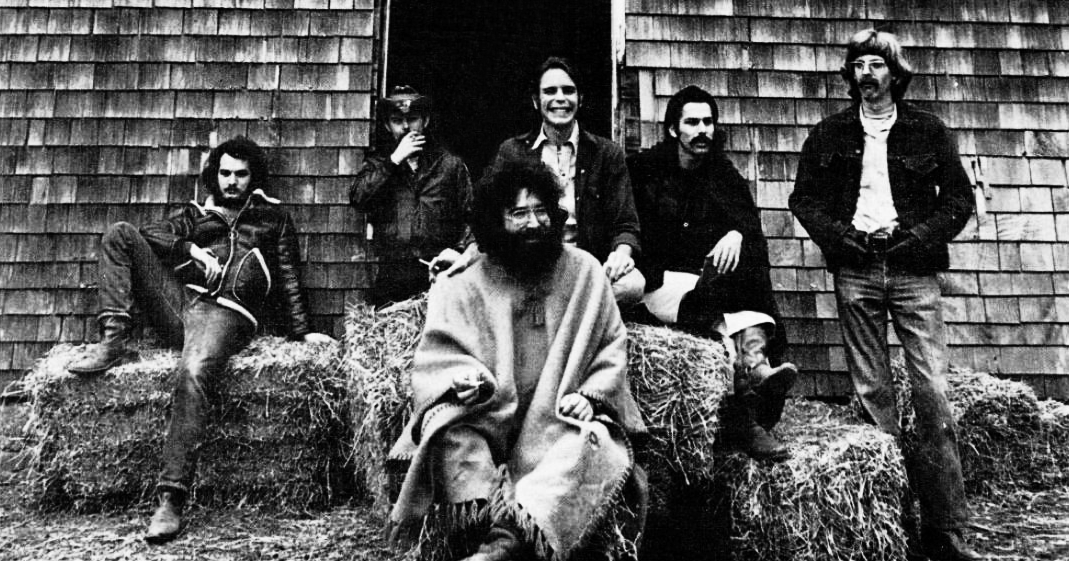

Then the Beatles and Stones washed ashore in 1964. A year later, Bob Dylan plugged his guitar into an amp at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival; Motown beamed the Detroit sound into every dancefloor in America; Brian Wilson took the Beach Boys into unchartered waters; the Grateful Dead tried LSD for the first time; and Bruce Spingsteen’s mother took out a loan to buy her kid his first guitar.

Rock and Roll was reborn, but with a harder edge, a more adventurous spirit, and substantially longer hair. It was in this moment that Rock and Roll became “rock”—something less formulaic, less immediately definable, and far more expansive. It became something more than some guitars and a drum kit. Rock became a palette of infinite colors inspiring boldness, experimentation, and the total deconstruction of barriers.

Rock is the catch-all terminology for everything that came after the first Golden Age—British Invasion, Girl Groups, Motown, Greenwich Village, Psychedelia, Progressive Rock, Soul, R&B, Metal, Punk, New Wave, Disco, Funk, Hip Hop, Alternative, and even Rock and Roll. So when we call something a “rock band,” let’s try to avoid any hangups about what we think ‘rock’ should sound like. Avoiding exactly those kinds of preconceived notions is what helped the artists on this list to earn our esteemed recognition, not to mention many lesser honors like unspeakable wealth and enshrinement in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Ok. You get the point. Rock is everything. Everything is rock.

Qualifications For Inclusion

- Be a Band

First, in order to be considered one of the 100 Best Rock Bands of All Time, one must be a band. Any group of people who play instruments, write songs, and perform concerts together qualifies as a band. Sooooo, for instance, Hootie & the Blowfish would qualify as a band. Wait. Come back. That’s just an example. They’re not on the list. Also qualifying for inclusion here are duos, vocal combos, rap crews, house bands, and whatever you’d call the colorful mass of humans that comprise Parliament/Funkadelic. Not eligible for inclusion are solo artists, which explains the conspicuous absence of Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and Rick Astley.

- Be Born After 1955

Also not eligible are bands whose output generally predates the proliferation of rock and roll. R&B groups like Billy Ward and his Dominos and vocal combos like the Ink Spots have an unquestionable place of importance in the early development of rock and roll. But there is an invisible line in history that bisects at the point where Elvis Presley first came to national prominence in 1955. Thus, only those who achieved their greatest musical accomplishments thereafter may be considered.

- Be Excellent;

Of course, everything I just said does nothing to prevent Hootie & the Blowfish from making the list. This is why our next qualification is critical. The top qualification for inclusion here is musical, instrumental, and/or artistic excellence. Bands included here helped raise the standards of songcraft, live performance, studio ingenuity, or virtuosity. Sometimes, artistic excellence is universal enough to transcend subjectivity. For instance, if you make a Top 100 list that doesn’t include Pink Floyd, it must be because Roger Waters ran over your dog. Otherwise, the consensus is that they were pretty darn excellent. The same is true of nearly all the artists included here.

- Or Be Successful;

I admit that not every band on this list is inherently excellent. But some bands are simply too successful to miss the cut. Some bands sold so many records that, no matter what you or I think of them, neither of us could deny their impact on popular culture. Yes, the Eagles are on this list. Yes, I recognize that they could be insufferably smug. But really, there’s just no way a band could sell 150 million records without doing a lot of things really right.

- Or Be Influential

Some artists on the list may defy any conventional definition of excellence or success, but must be ranked for the cultural impact of their work. Sid Vicious was such a crummy musician that his fellow Sex Pistols would famously turn down the volume on his amp during live performances. But the depraved bassist also perfectly embodied the nihilism and rage that made his band monumentally influential. In order to be included on this list, being excellent helps. But if you don’t have that, making an earth-shattering impression on the course of history is the next best thing.

Ranking

Our ranking procedure was extremely scientific in that I wore a lab coat and safety goggles.

Consistent with our broader mission here at Music Influence, the goal was to rank artists by influence. When we rank one artist above another, we are not making the argument that the former artist is better than the latter. Instead, we’re arguing that the higher-ranking artist is more influential. Thus, when we place hip hop pioneers Run D.M.C. ahead of alt-radio godfathers R.E.M., we are not arguing that Run D.M.C. is better. Instead, we are claiming that the Hollis, Queens trio did just slightly more to change the face of popular music than did the quartet out of Athens, Georgia.

That said, unlike other rankings on our site, this list isn’t powered by our algorithm. Instead, influence is informed by a set of unweighted variables including commercial success, artistic importance, cultural relevance, and personal preference. Yeah, that’s right, there’s some bias in here. If you don’t like it, write your own list. Seriously. I’m not being pithy. It’s a really fun exercise and I wish you the best.

But this is my list so you’re bound to disagree with some of my choices. You probably think I’m crazy to rank this band over that band. You might think I’m an idiot for ranking a band you hate ten spots above a band that you’d sell a kidney (perhaps even your own) to see live. You might wish to send me hate mail for failing to find the space in 100 entries and 50,000+ words to even mention the band that you’ve dedicated your adult life to worshiping. (Rush fans—please direct your Dr. Who-reference-riddled diatribes directly to our webmaster).

Well that’s the beauty of a list like this. There’s no way it’s going to be 100% right but you can’t prove it’s wrong. This means we get to have a fantastic and impossible-to-settle debate about rock music, about what it is, where it’s been, and where it’s going.

Enough introducing. Let’s get right into the bands.

The Best Rock Bands of All Time: 25-1

25. Mothers of Invention

It’s hard to think of a man whose weirdness and talent came in such equally enormous proportion as did Frank Zappa’s. It was only fair, then, that the Baltimore-born guitar virtuoso should have a band capable of similar brilliance and oddness. He found it when he joined the members of an underground California rock band called the Soul Giants. Changing their name to the Mothers of Invention, they transformed into a vehicle for Zappa’s deconstructionist and avant garde predilections.

In the Mothers, Zappa had a band capable of veering effortlessly between greasy blues riffs, bubbly psychedelic hard rock, cartoonish prog, and tongue-in-cheek folk. Combining their forces in 1966, the Mothers of Invention released a series of critically acclaimed records that lampooned the musical and cultural conceits of the 1960s while simultaneously indulging in and expanding upon the decade’s sonic excesses.

On Freak Out! (1966), Absolutely Free (1967), and We’re Only In It For the Money (1968), Zappa demonstrated stunningly virtuosic skills as a guitarist and distinguished his records with a goofily stentorian voice that seemed always to be drenched in sarcasm.

Behind Zappa, the Mothers of Invention endured three dramatic shifts in their lineup during one decade of existence. At all times, Zappa, a famously stern workaholic, surrounded himself with a combination of top-flight musicians and first-rate weirdos. Among the most famous individuals to fall into the latter category was gruff-voiced singer Captain Beefheart, who would thereafter go on to record several deeply influential avant rock albums with his Magic Band.

Other famous Mothers include Roy Estrada and Lowell George, who would go on to found dixie oddballs, Little Feat; Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, formerly of the Turtles and, thereafter, principals of Flo & Eddie; fusion master George Duke; noted solo electric violinist Jean Luc-Ponty; Henry Vestine, thereafter of Canned Heat; and jazz-rock drummer extraordinaire, Terry Bozzio.

These various incarnations did something particularly unlikely for a band as off-the-wall, in-your-face, and out-of-left field as the Mothers. They had hits, sort of. After nearly a decade as one of the world’s most critically acclaimed and commercially misunderstood groups, Zappa’s embrace of prog-rock stylings yielded an unlikely top-ten hit with “Apostrophe (‘)” (1974) and its equally unlikely hit single “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow.”

The following year, Zappa disbanded the Mothers but continued to discover and showcase stellar young musicians like the Brecker Brothers and Steve Vai. His work dealt the same savage satirical eye and inscrutable musical dexterity to experiments in hard rock, fusion, new wave, and classical music, gradually building a case for Zappa as one of the most profound, profane, and prolific artists in the world. His reputation as a decidedly well-spoken representative of his industry was reinforced by a 1987 Congressional appearance, alongside John Denver and Dee Snider of Twisted Sister, in opposition to government efforts at music censorship.

Even as Zappa sharply critiqued the material excess and musical superficiality of his rock and roll peers, he defended their right to be thus. Zappa died of cancer in 1993 and entered into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame two years later.

Photo By: Ron Kroon / Anefo – Nationaal Archief, CC0

24. The Band

The Band began its existence as a rough-and-tumble Canadian backing unit and ended its run as an American institution. For a group of guys from above the northern border—excepting Arkansas-born drummer Levon Helm — the Band seemed to command an unparalleled grasp of America’s rural mystique.

Helm joined Rick Danko (bass), Garth Hudson (keyboards), Richard Manuel (piano), and Robbie Robertson (guitar) in the late ’50s to support rockabilly madman Ronnie Hawkins. It was thus that they were dubbed the Hawks, touring Canada’s dive bar scene and earning a reputation as among the roughest, rowdiest, and most authentic rock and roll combos in the game.

In 1964, determining that they had graduated from backing service, the group stepped out from behind Ronnie Hawkins, first billing themselves as Levon and the Hawks, then as the Canadian Squires. Touring the U.S. on the strength of a lofty underground reputation, the Hawks met ascending Greenwich Village bard, Bob Dylan.

Over the next two years, Bob Dylan electrified the music world (literally), by plugging in his amp and veering from protest folk into speed-fueled rock surrealism. As Dylan expanded his repertoire, his audience, and rock music’s lyrical palette, he ignited fury among folk purists, who labeled him a sell-out and a traitor to the protest movement. As concert audiences intermittently cheered or booed Dylan, the members of his backing group stood alongside him and absorbed the abuse.

Today, history views this period as a milestone in both Dylan’s career and the broader trajectory of rock music. History, therefore, also smiles upon his backing band for their bold contributions. The former Hawks earned the name The Band for their singularity within Dylan’s touring retinue. After two solid years spent facing down hostile audiences and critical misinterpretation, Dylan and the Band retired to a house in Saugerties, New York dubbed Big Pink. There within, the musicians entered into a period of unparalleled fertility, improvising and recording a seemingly endless batch of songs inspired by lost history, ancient headlines, sea shanties, murder ballads, and a host of sepia-toned memories that are of a distinctly forgotten and extinct American life. The authenticity of their recordings was underscored by the fact that they never expected any of them to be heard. This was merely a sustained exercise in creative interchange.

Over the next year, an audience desperate for a followup to Dylan’s “Blonde on Blonde,” gobbled up bootleg copies (which became known as “The Basement Tapes”) with such ferocity that its sessions were finally anthologized by way of an official release a decade later. As for the Band, they finally had the chance to strike out on their own in 1968. Their debut, Music from Big Pink, established their image as a cast of displaced Civil War veterans. Rooted by the road-weary “The Weight” and rounded out by a trio of Dylan-penned masterpieces, Big Pink celebrated Americana with bucolic majesty.

In 1969, the Band appeared at the Woodstock music festival, an easy trip given that it was practically held in their backyard. That same year’s “The Band” deepened their pastoral image with a batch of songs drenched in backwoods mythology and populated by country gentlemen, most notably the mournful “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and the buoyant “Up On Cripple Creek,” the latter of which landed the out-of-time band at #25 on the charts.

The Band earned its eventual passage into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame over the course of the next decade with a steady stream of records–Stage Fright (1970), Cahoots (1971) and Northern Lights – Southern Cross (1976)–and a well-earned reputation as a road-tested warhorse. This reputation is well-captured on 1972’s double-live release, Rock of Ages.

However, their broader influence is perhaps best celebrated, as is the excess of the era in general, in The Last Waltz, a Martin Scorsese directed documentary showcasing the Band’s farewell performance. Filmed in 1976 and released two years later, The Last Waltz would feaure appearances by Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Van Morrison, and even old Ronnie Hawkins. To date, it remains a standard-bearer among live concert releases.

Though the Band would reunite at various points thereafter, today only Robbie Robertson and Garth Hudson are still with us.

Photo By: Capitol Records – Billboard, page 19, 28 November 1970, Public Domain

23. Talking Heads

The Talking Heads were the most literate, intelligent, and playful of the CBGB set. Led by idiosyncratic singer, songwriter, and giant-floppy-suit-wearer, David Byrne, the Talking Heads may be among the greatest influences coursing through today’s rock radio consciousness, best representing the nervy arthouse ethos of New Wave, the lyrical obscurity of alternative, and the hookiness of today’s beardly hipster bands. All owe a debt to the Talking Heads for their right to be weird and successful all at once.

The Talking Heads formed in 1975, joining Byrne’s off-kilter vocals and quirky songwriting with Jerry Harrison’s layered keyboards, Tina Weymouth’s funky bass, and Chris Frantz’s staccato time signatures. The group rose to recognition as part of the New York punk scene that birthed legends like the Ramones, Television, and Blondie. Among them, the Talking Heads stood out for their intelligence and conscious artiness. In 1977, their breakthrough hit, “Psycho Killer”, burned up the charts while the Son of Sam terrorized New York.

Over the course of eight albums, David Byrne was responsible for the lion’s share of writing as well as for his band’s musical eclecticism. Albums like Fear of Music (1979) and Speaking in Tongues. (1985) produced substantial charting hits while incorporating elements of Brazilian music, African poly-rhythms, and the synthesizers that would define new wave.

The Talking Heads were perhaps the most essential trailblazer in a post-punk genre that shot the Police, Duran Duran, and the Cars to megastardom. Byrne’s contributions to the MTV era may best be captured in the band’s groundbreaking Stop Making Sense (1984), an ingenious concert documentary (not to mention album) directed by Jonathan Demme. Its imagery and performance aesthetics make it a template-setting document in the music video medium.

Though the Talking Heads disbanded at the end of the ’80s, Byrne’s solo career continues to distinguish him. Starting with 1981’s highly influential ambient record, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1981), Byrne has lent his name to a series of solo works that touch on all manner of world, electronic, and even dance music. The Talking Heads were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002.

Photo By: By Plismo – Own work, CC BY 3.0

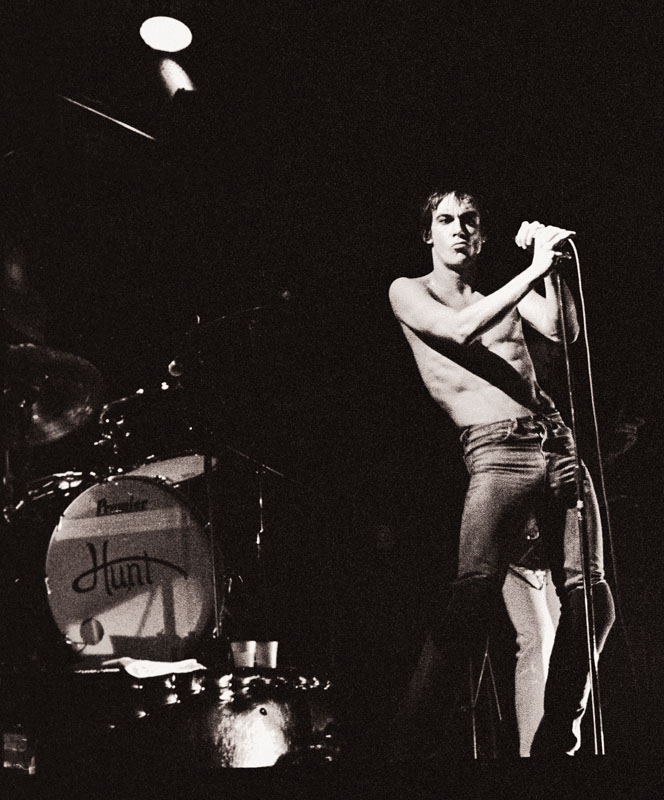

22. Iggy Pop And The Stooges

The Stooges were the brainchild of rock and roll’s wildest child, Iggy Pop. The Ann Arbor combo played a special brand of apocalyptic garage rock that prefigured punk music’s attitude and aesthetic by a decade. Today, their work offers us an ingenious study in controlled chaos.

Joining local friends and brothers, Ron and Scott Asheton, and bassist Dave Alexander, Iggy formed the Psychedelic Stooges in 1967 (They eventually dropped the ‘Psychedelic’ from their handle). The Stooges pulled in elements of psychedelia, electric blues, and surf rock, churning their ingredients in a blender and splattering them all over unsuspecting crowds.

Iggy Pop proved a natural innovator in the field of performance art, taking a cue from Jim Morrison and embarking on some of the most aggressive and confrontational music ever thrust before an audience.

While the Stooges bludgeoned listeners with their savage instrumental attack and deliriously loud arrangements, Iggy would shatter bottles and cut himself with the broken glass, strip down to nothing and dive into the crowd. In fact, legend has it that Mr. Pop invented the stage dive and, consequently, the crowd surf, both eventual staples of the punk, grunge, and alternative concert experience.

More importantly, the band’s studied primitivism, musical minimalism, and show-stopping insanity verily wrote the book on punk rock roughly a decade before the term entered music’s popular lexicon. As par for the punk course, the Stooges recorded two landmark albums that nobody bought before completely imploding. But with The Stooges (1969) and Fun House (1970), Iggy and his band scribed the preamble for the future punk revolution.

Though neither of these records reached a mainstream audience, Iggy’s legend as a terrifying and exhilarating performer did grow. So too did his heroin addiction, a fact which led to the group’s demise in 1971. In the same year, Iggy met David Bowie, who was just then on the path to massive success. Bowie offered to share this success with his new friend and produced an Iggy and the Stooges reunion, minus Dave Alexander. 1973’s Raw Power was the result. Once again, Iggy upped the ante, producing an album of gritty, howling intensity that sold very few copies but had career-making influence on those who did buy it.

This was also the beginning of an incredibly valuable association with David Bowie. Iggy and the Stooges broke up a second time, again due to Pop’s heroin addiction. It was thus that he sought treatment at a mental institution, a time in which Bowie was one of his few constant visitors. Future collaborations with Bowie would produce Iggy’s finest solo work when, in 1977, he released both The Idiot and Lust for Life.

Iggy also got the chance to reunite with his old buddies from the Stooges, embarking on a triumphant reunion tour in the early and mid-2000s that allowed the band to bask in the glow of a reputation 30 years in the making while exposing its music to a whole new generation of listeners. Though verging on 60 years of age at the time, Iggy’s performances were as artistically destructive and confrontational as ever, living proof that he is punk’s first wild child.

In 2010, Iggy Pop and the Stooges were collectively inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Photo By: Michael Markos, CC BY-SA 2.0

21. The Supremes

They weren’t the first. That title belongs to the Shirelles. And they weren’t necessarily blessed with the rawest talent. One might argue that front-women like Gladys Knight and Martha Reeves could sing circles around Diana Ross. But the Supremes were invariably and unarguably the most successful of the girl-groups, outfitted with the best material, and ultimately, destined for the brightest star. Beyond that, the Supremes are the single most successful vocal harmony group in history.

Their history coincides with that of history’s other most successful vocal harmony group. As Detroit natives Paul Williams and Eddie Kendricks began singing in a group called the Primes (one day to become the Temptations), friends Florence Ballard, Mary Wilson, and Diana Ross formed the Primetttes in 1959. Ross reached out to her friend and neighbor Smokey Robinson, asking him to pass a demo to Motown magnate Berry Gordy. Though Gordy liked the girls, he felt they were too young for his label.

Unrelenting, the newly-dubbed Supremes persisted on showing up at the studio on a near-daily basis, forcing Gordy to employ their services as back-up singers and hand-clappers on hits by the likes of Marvin Gaye. By 1963, the Supremes had released a series of Robinson and Gordy-authored go-nowhere singles. But the group’s tenacity, the rising reputation of Diana Ross, and a partnership with ace songwriting team Holland-Dozier-Holland would lead to a huge break in 1964. That year, “Where Did Our Love Go” took the Supremes to the top spot on the charts and crossed over to #3 in the U.K.

Four consecutive #1 hits followed with “Baby Love”, “Come See About Me”, “Stop! In the Name of Love” and “Back In My Arms Again.” The Supremes were quickly becoming Motown’s most prominent act, with their elegant and polished image underscoring Motown’s strategy for attracting integrated audiences. As the Beatles scaled up the charts, the Supremes emerged as one of the few American acts capable not just of surviving but of actually competing with the British Invasion.

As the chart-toppers continued into the mid-1960s, with hits like “You Can’t Hurry Love,” “I Hear a Symphony” and “You Keep Me Hangin’ On” all but defining the Motown sound, the Supremes were global stars who inherently dismantled racial barriers by way of primetime television appearances and international headlining gigs. It was their success that would ultimately help Motown soundtrack the decade by way of future superstars like the Temptations and the Jackson 5.

Trouble began to brew within the group however, much of it owing to Diana Ross’s ever-growing fame. As Gordy quietly schemed to advance the leader’s solo career, jealousy fomented within. Florence Ballard, feeling her role increasingly marginalized, descended into alcoholism before ultimately being replaced by former Patti Labelle & the Blue Notes singer, Cindy Birdsong. It was also at this time, in 1967, that the group officially began taking billing as Diana Ross & the Supremes.

Even within the larger Motown community, artists grumbled that Gordy’s favoritism for his beloved Supremes often earned the group the label’s very best songwriting output. Their pairing with some of the greatest pop songs ever composed has as much if not more to do with the Supremes’ success than did their own talents. Indeed, as evidence of this fact, the contractual dispute with and departure of Holland-Dozier-Holland from Motown would impact the Supremes directly.

As the perfect pop compositions dried up, so too did the relevance of the Supremes in an era where Black music was becoming increasingly radical, revolutionary, and politically explicit. In 1969, the group had its final #1 of the decade with the ironically-titled “Someday We’ll be Together.” By the start of the next year, they no longer were.

Diana Ross departed for an enormously successful solo career and the Supremes enjoyed chart success on name recognition through much of the remaining decade, finally disbanding in 1977. Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, the Supremes easily top all other vocal combo acts with 12 #1 pop chart hits.

Photo By: CBS Television – eBay itemphoto frontphoto back, Public Domain

20. The Temptations

In the early 1960s, male vocal combos were a dime a dozen, especially in Detroit. But the members of two rival groups, the Primes and the Distants, would combine to achieve unparalleled fame and success.

Of course, the Temptations have experienced success almost regardless of the singers performing under the well-traveled name. However, the five men who saw the group through its classic mid-60s hits, and the slightly adjusted line-up that would transition them into the 1970s, possessed among the most magically compatible voices in the business.

In 1961, Eddie Kendricks and Paul Williams joined Otis Williams, Elbridge Bryant and Melvin Franklin in the Motown stable. They recorded and performed tirelessly for the following two years but saw little return for their efforts.

Frustrated by their slow ascent, Bryant became disillusioned and, following a conflict in which he bludgeoned Paul Williams with a beer bottle, was dismissed over the 1963 Christmas holiday. It was with his replacement, David Ruffin, that the Temptations broke through in a huge way.

This lineup is largely considered the Temptations’ most important. Teaming with songwriter and producer Smokey Robinson, the Temps increasingly dealt in material compatible with Ruffin’s raw but soothing vocal style. Thus, the group had its first Top 20 single with the inscrutable pop gem, “The Way You Do The Things You Do.” Robinson and company repeated the formula on “My Girl” in December of 1964. By spring of the following year, it had become the Temptations’ first chart-topper.

As the Temptations emerged from unknowns to lead horses in the Motown stable, the label paired them with songwriter Norman Whitfield, helping the Temps to transition from the pop conventions of their earlier work into more complex and densely layered material like “I Wish It Would Rain.” The start of this partnership would also coincide with the end of Ruffin’s run. A combination of cocaine and ego led to Ruffin’s ouster. Dennis Edwards of the Contours was hired as his replacement, though this didn’t stop Ruffin from stalking the group through its 1968 tour and popping on stage without invitation, stealing the microphone, and performing “Ain’t Too Proud To Beg” on several dates.

Nonetheless, Ruffin faded into a solo career while Edwards took over lead duties for a band probing new territory. Increasingly influenced by the psychedelic swing of Sly and the Family Stone, and the grittier variety of soul coming out of Stax Records in Memphis, Motown saw the Temps as the perfect outlet for its tripped out, fuzz-heavy productions. With Whitfield at the pen, the Temps enjoyed hits with “Cloud Nine”, “Psychedelic Shack”, and, most importantly, 1972’s “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.”

Just as the Temptations had soundtracked a more innocent era with perfectly pitched love songs, the group’s new material was aptly suited to the heady and chaotic early 1970s. Their focus increasingly turned to songs addressing the troubling realities of black urban life, a far cry from the matching suits and choreographed dances of their early days. So different was the material that Eddie Kendricks, increasingly uncomfortable with the shift in focus, departed for a successful solo career in the early ’70s.

By 1974, the remaining Temptations had parted ways with Whitfield, moving into a more contemporary disco sound. This would mark the end of their days as one of popular music’s most irrepressible hit-making operations, with a few charting exceptions in the ’80s and ’90s. Like pretty much every other vocal combo of note, their name ultimately became far more important than the individual members of the group, with revival and oldies acts touring almost constantly for the past 40 years. Today, the group that calls itself the Temptations boasts a single original member in Otis Williams.

Both the classic Ruffin lineup and Dennis Edwards were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1989, with four #1 pop singles and 14 #1 R&B singles to their credit.

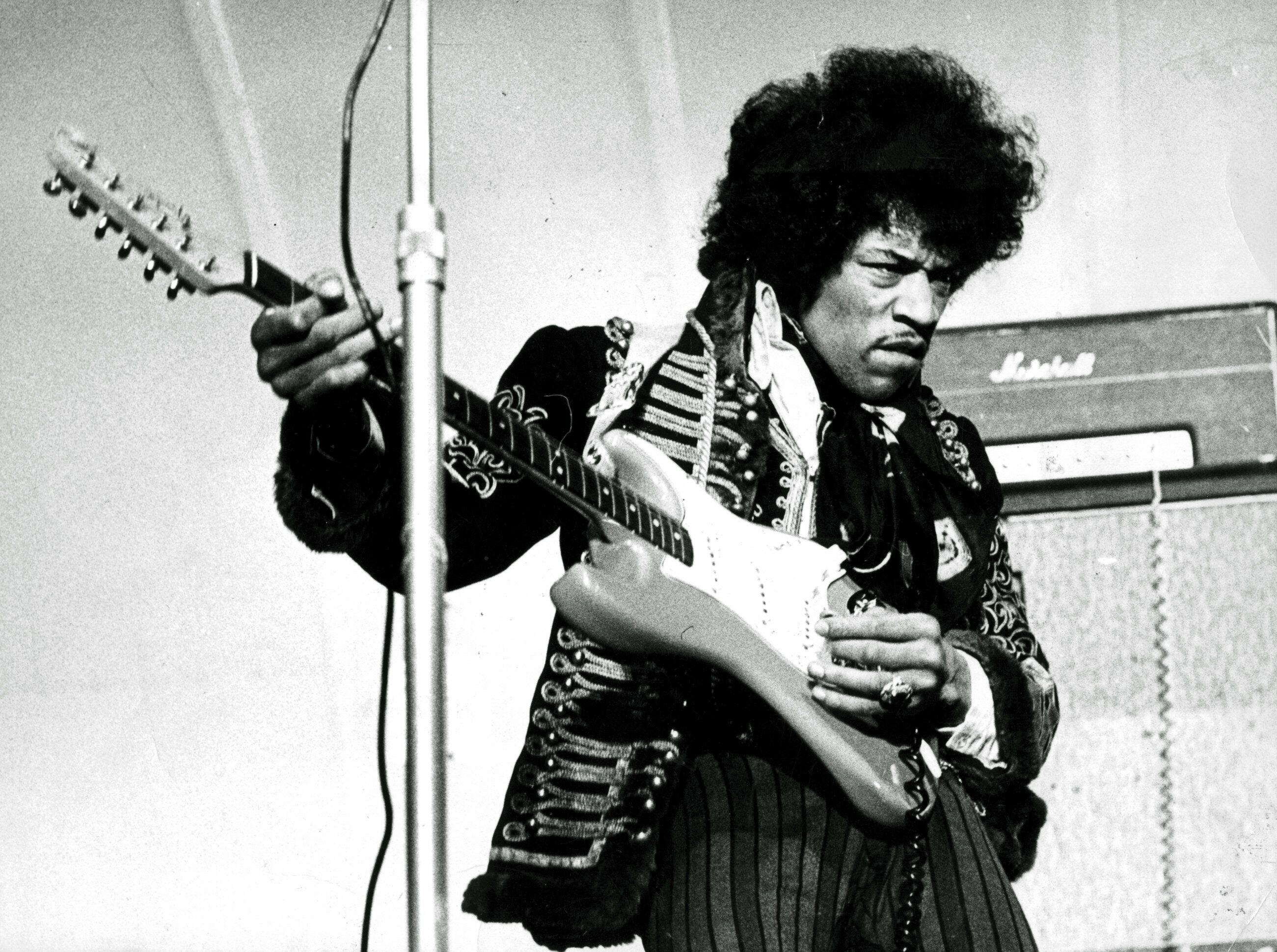

19. Jimi Hendrix Experience

Simply stated, the Jimi Hendrix Experience was the platform for the single greatest guitarist in the history of rock music. The band truly existed for no longer than four years but their impact was monumental. The Experience came to be when a hotshot young Seattle-born guitarist, fresh off of stints backing the Isley Brothers and Little Richard, journeyed to London in search of fame. To say the least, he found it there. With Chas Chandler of the Animals assuming managerial duties in 1966, Hendrix was paired with two musicians of considerable acclaim and compatibly freaky fashion sensibilities in bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell.

Striking out as a power trio much in the vein of Cream, the Jimi Hendrix Experience promptly conquered the U.K. In just a few short months, the lead singer, songwriter and guitarist had set London abuzz with his fleet and fluid shredding. Hendrix showed an uncommon penchant for instrumental innovation, verily expanding commonly accepted notions about what a rock guitar could or should be made to do.

His coming out party came in early 1967 at a London club called The Bag O’Nails. In attendance was pretty much every single British musician of relative influence at the time, including John Lennon, Mick Jagger, Eric Clapton, Pete Townshend, and Jeff Beck. Clapton famously leaned over to Townshend as Hendrix evinced otherworldly squeals and fret-bursts from his guitar and predicted that the man would soon put the rest of them out of business.

Releasing their debut album, Are You Experienced? in the spring of 1967, the Experience capitalized on its rising notoriety by scoring three U.K. hits in “Purple Haze”, “The Wind Cries Mary”, and the definitive, spot-on electrification of Billy Roberts’ oft-covered “Hey Joe.” With the success of their debut, it was time for the Experience to cross the Atlantic. Though enjoying a meteoric rise in England, Hendrix was still relatively unknown in the U.S.

The Monterey Pop Festival in the summer of ’67 changed all of that. His performance is still widely considered among the most iconic moments in rock history. At the end of a set that shattered sonic borders in an angel dust-induced cascade of distortion, effects pedals, and martian soloing, Hendrix knelt down, set his guitar on fire, and summoned its flaming spirit like a possessed shaman. The performance would become a defining moment in an era of unbridled innovation, with Hendrix quickly rising to the top of the psychedelic ranks.

His next two records with the Experience, Axis: Bold As Love (1967) and Electric Ladyland (1968), swam deeper into psychedelic waters. Hits like the never-to-be-equaled adaptation of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” and “Burning of the Midnight Lamp” made the latter of these a #1 record. For a brief time, Hendrix was the highest-paid performer in the business, with each of his live engagements raising the bar for dizzying instrumental exploration. Mitchell’s sumptuous jazz licks and Redding’s out-front bass lines proved equal to the task and helped imbue Jimi’s own work with a modish sensibility. The trio also cast a visual spectacle with their teased up afros, sweeping coats, and multi-colored tunics, helping to model the hippie movement’s most flamboyant fashions.

Not to be overlooked in the context of said movement was the all-important drug culture, to which Hendrix himself became inextricably linked. His love for LSD and the violent mood swings he often experienced while drinking began to cause rifts within the Experience, leading to their split in 1969. Hendrix gathered together his Band of Gypsies for another epochal performance, this time at Woodstock.

After recording one live album with the Gypsies, rumors and press releases swirled with word of an Experience reunion. This was not to be. In September of 1970, Hendrix, exhausted from touring, shared a bottle of wine with his girlfriend before overdosing on sleeping pills and asphyxiating in his sleep. At 27, rock music’s greatest instrumentalist was gone. Redding and Mitchell have since passed on as well, though all are immortalized by a shrine in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Photo By: Original photographer unknown – e24.se, attributed to Scanpixtrelleborgsallehanda.se, Public Domain

18. Booker T. & the M.G.s

When you think of Southern Soul, you probably think of guys like Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave, and Otis Redding. You’d be right to think that. But these guys all had something in common. They all recorded with the nastiest house band in the world. As the backing group for the remarkable roster of talents that roamed the halls of Soulsville (Stax Records in Memphis), Booker T. Jones (organ), Al Jackson, Jr. (drums), Steve Cropper (guitar), and Donald “Duck” Dunn (bass) did nothing less than build the sound of Southern Soul.

Formed in 1962, the original lineup featured Lewie Steinberg, rather than Dunn, on bass. It was this lineup that gathered for the first time together at Stax to back rockabilly wild man Billy Lee Riley. In between takes, with tape still rolling, they improvised a slow, grooving instrumental that came to be called “Green Onions”.

Released as a single, “Green Onions.” gave the band a #1 R&B/ #3 Pop Billboard entry. Booker T. effectively and repeatedly followed the formula of the million-seller with a decade’s worth of smoky, organ-driven instrumental hits.

Their success as a charting act was merely icing on the cake though. In reality, their contributions to popular music during the mid and late ’60s have few equals. Working on the Black side of the tracks in Memphis, Booker T., and Stax on the whole, represented an island of racial harmony in a turbulent time. The band itself was integrated, a fact which predisposed Stax to bold, inventive, and boundary-crushing soul music. Especially with the departure of Steinberg and the beginning of Dunn’s tenure in 1965, the M.G.s became the engine behind the Memphis soul machine.

In addition to the aforementioned soul men, Booker T. performed on hundreds of records by artists including Johnny Taylor, Albert King, William Bell, and Rufus Thomas. Future badass Isaac Hayes also performed frequently with the M.G.s. Their work stands out on classic recordings like Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man”, Rufus Thomas’ “Walking the Dog”, and Redding’s breathless “Try a Little Tenderness.” Their role also earned them a spot as Redding’s supporting band during his famously triumphant 1967 appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival.

As Stax collapsed internally at the turn of the decade, the house band began to splinter. Still, the M.G.s did continue to release records under their own name, including the stellar Abbey Road tribute, McLemore Avenue (1970) and Melting Pot (1971), a minor soul-funk classic with heavy future implications for hip hop samplers.

In 1975, as the band prepared for another release, the great drummer Al Jackson, Jr. was gunned down in his own home. His fellow M.G.s toured and recorded every few years with a rotating cast of drummers. Their most notable work during the next decade came as the backing band for John Belushi and Dan Akroyd. Dunn and Cropper were, in fact, official Blues Brothers and showed off their acting chops in the hit 1980 film.

Its vaunted reputation, in fact, would earn Booker T. & the M.G.s the somewhat de facto role as house band for many of rock and roll’s greatest historical celebrations, including the Atlantic Records’ 40th Anniversary Celebration (1986), Bob Dylan’s 30th Anniversary Concert (1992), and the opening ceremonies for Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame museum (1995). They themselves had been enshrined into the work-in-progress museum just three years earlier.

Photo By: Stax – Billboard, page 9, March 11, 1967, Public Domain

17. The Funk Brothers

The Funk Brothers have played on more #1 hits than the Beatles, Elvis Presley, and the Rolling Stones combined and it’s entirely possible that you’ve never even heard of them. Such is the fate of the most successful house band popular music has ever known.

The collection of studio musicians who held court at Detroit’s Motown records from 1959 to 1972 gave life to the label’s unrivaled silo of hits. Smokey Robinson, the Temptations, Marvin Gaye, the Jackson Five, the Supremes, Martha and the Vandellas, the Four Tops; all were beneficiaries of the tightest, tautest, most tasteful backing band in the game.

If Booker T. and the M.G.s embodied the gritty soul of the South, the Funk Brothers defined Northern polish with bright, chiming brilliance. Remarkably, their work went largely uncredited throughout the ’60s, even as they provided architectural foundation to Hitsville on songs like “My Girl” (The Temptations), “Signed, Sealed, Delivered” (Stevie Wonder), and “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”, (Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell). As a result, the 13 musicians who are officially regarded as Funk Brothers by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences are not at all household names.

Most famous among them are likely the alliterative twins of Motown backbeat, drummer Benny Benjamin and bassist James Jamerson. Other notables include piano player Earl Van Dyke, guitarist Eddie “Chank” Willis and guitarist Dennis Coffey, the latter of whom provided some of the most searing riffs of the label’s late psychedelic-soul period. By extension, the true list of players in the Motown house is far longer. And the sum of its accomplishments is fairly staggering, with its musical output all but defining American soul, R&B, and rock in the decade of their greatest artistic growth. Motown’s songs and artists are, more than any other single body of work, the soundtrack to the 1960s.

From the debonair delights of early Temptations to the social call to action of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Goin’ On? (1971), from the urgency of Diana Ross and the Supremes to the longing of Gladys Knight & the Pips, the Funk Brothers remained famously anonymous, standing, as a 2002 documentary on their contributions would say, “in the shadows of love.” Though Benny Benjamin and James Jamerson are both deceased, each was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The core 13 Funk Brothers have also been honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Their contributions to the sound and musical vocabulary of popular song is absolutely incalculable.

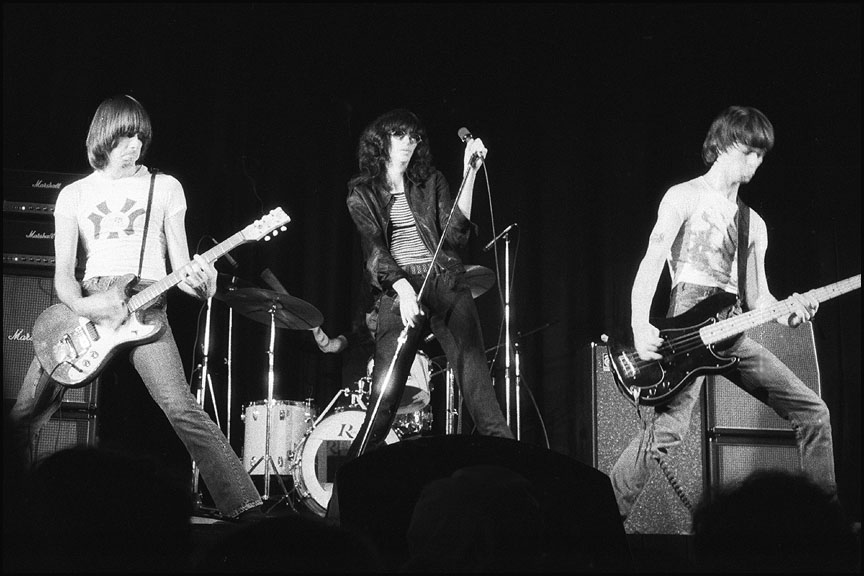

16. The Ramones

All the Ramones needed to change the world were three chords and a really bad attitude. Theirs was the simplest and most satisfying of revolutions, even if the band itself never truly enjoyed commercial success on equal footing with the admiration heaped upon it and the influence spread out before it.

Though our list of bands must necessarily include seminal proto-punk influences like the Stooges and the New York Dolls, the Ramones are the first true punk band. The Queens quartet formed in 1974 and abandoned their respective surnames in favor of the band’s (though an awesome and apocryphal story tells that the four original members actually met in an elevator, realized they all had the same name, and decided to start a band).

Whatever the case, Joey Ramone (vocals), Johnny Ramone (guitarist), Dee Dee Ramone (bassist), and Tommy Ramone (drummer) were an absolutely unique enterprise from the day of their inception. Draped in leather jackets and ripped jeans, instruments slung low so that they stooped like cavemen, the Ramones bludgeoned audiences with an attack that was as loud, fast, and raw as anything yet heard or seen. Their songs, short and severe though they were, also owed a tuneful debt to early rock and roll, girl group, garage rock, and bubble gum music. Condensing all of these elements into songs that rarely crested the two-minute mark, The Ramones quickly became one of the most exciting and talked-about acts in the burgeoning and as-yet unnamed New York scene.

The word punk would stick right around the time the Ramones were sonically assaulting their first audience at the famed punk club, CBGB. The band played no fewer than 70 gigs at the landmark venue that year before ultimately landing a contract with Sire and releasing their self-titled debut in 1976. Though it contained future punk classics like “Blitzkrieg Bop” and “Beat on the Brat”, and though it earned lavish critical attention, it was largely ignored by listeners.

It wasn’t until a tour in England the following year that the Ramones learned how big an impact their first record and their attendant image had made. During a London show attended by the young and impressionable members of the Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Damned, and the Jam, the Ramones all but christened the U.K. punk explosion of the coming year. The next two records saw the Ramones’ profile rising in the U.S., though still with little money to show for it.

Often regarded as their most classic record, Rocket to Russia would mark their highest charting success to that point, reaching #49 and yielding the band’s biggest U.S. hit, “Rockaway Beach.” Russia perhaps best embodies the dynamic that made the Ramones the perfect punk unit, offering a rapid-fire collection of songs that paired minimalist intensity with infectious hookiness. Replacing drummer Tommy with Marky Ramone, the group entered the studio with legendary but, by then, increasingly unstable producer Phil Spector in order to capitalize on their emergent success.

Released in 1980, End of the Century would rank as the band’s biggest charting success, reaching #44, but Spect0er’s dense production was a poor fit for the band. Contributing to this negative impression was probably the fact that Phil Spector pulled a gun on Johnny Ramone during the sessions, something which the producer was not unknown to do on occasion.

Though the Ramones would continue to record, and to enjoy the adulation of a new generation of musicians during the punk-fueled alternative boom, they never recaptured the magic of their days at the CBGB nor did they ever achieve the commercial success that seemed inevitably to be their birthright. Sadly, as other bands of their ilk have enjoyed lucrative reunion tours in their golden years, the Ramones will have no golden years. Joey died of lymphoma in 1999. The four living Ramones all appeared together upon their 2002 induction in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame but Dee Dee would be dead from a heroin overdose two months later, Johnny felled by prostate cancer two years hence, and Tommy from bile duct cancer just last year.

Perhaps their greatest legacy as punk’s premier act, however, is the living proof that any kid can start a revolution with a guitar and three chords.

Photo By: Plismo – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

15. Sly and the Family Stone

In the late 1960s, the hippie movement dreamed of a utopia of harmonious racial and gender equality propelled by peace, love, and music without boundaries. If ever a band embodied these ideals, it was Sly and the Family Stone.

Multiracial, multigendered, and multilateral in its musical experimentation, Sly and the Family Stone was among the most daring, exciting, and downright fun ensembles of their time. Blending funk, soul, rock, and psychedelic experimentation into a single flower power package, Sly harbored the good vibes we associate with the hippie movement at its very best.

Formed in 1967, Sly and the Family Stone was the brainchild of Bay Area DJ and producer (of lite-psych fare like the Beau Brummels and Mojo Men), Sly Stone. Teaming with brother Freddie (guitar), sister Rose (keys), Cynthia Robinson (trumpet), Gregg Enrico (drums), Ronnie Crawford (sax), and Larry Graham (bass), Stone formed a band that, much like his radio show, blended rock and psychedelia with gospel, funk, and soul. The result was an utterly original sound and message that turned popular music on its ear.

Though their 1967 debut, A Whole New Thing, attracted considerable praise from journalists and fellow musicians, it was not until 1968’s “Dance to the Music” that the band broke through to national attention. The song reached #8 on the charts and though it was only their first hit, it touched off a significant transformation of Black music. Even for established hit factories like Motown and Stax, Sly and the Family Stone signaled a new and progressive deconstruction of musical boundaries. The labels famous for leading innovation followed in Sly Stone’s footsteps, pairing artists like the Temptations (in the case of Motown) and Isaac Hayes (in the case of Stax), with big fuzzy guitars. Psychedelic soul had been invented, eventually clearing a path for Funkadelic and all that would come thereafter.

In 1969, Sly reached even greater heights with the record Stand! and accompanying single “Everyday People.” Its egalitarian message captured as succinctly as anything the mood of peace and unity permeating the counterculture. Its acclaimed spot on the stage at Woodstock underscored this message. The Family Stone’s integrated and coed lineup made for a striking image at the watershed festival. Tunes like “I Want to Take You Higher” stood out as milestone musical moments both at the festival and within the broader era.

As the glory days of the ’60s turned to the ’70s, the band moved toward a grittier and more funk-driven sound. Though this sound hinted at the growing drug use within the band, it also produced a body of highly regarded post-hippie work, much of it frequently sampled in hip hop circles. There’s a Riot Goin’ On traded the optimism of the previous era with a far darker and bluesier foreboding, but nonetheless debuted at the top of the charts upon its 1971 release. Sly Stone’s cocaine addiction led to growing tension within the band, culminating in the departure of the band’s virtuosic and influential bassist. Larry Graham left to form the funk outfit, Graham Central Station.

After an additional two albums, drug abuse had ruptured the band’s unity, performance consistency, and concert attendance. By 1975, the Sly and the Family Stone was finished, with many of its members going on to work steadily as session and touring musicians. As for their visionary leader, his life since fame has been one long story of destitution and drug addiction, though he did make a surprise appearance before stunned audience members and bandmates at the band’s 1993 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction.

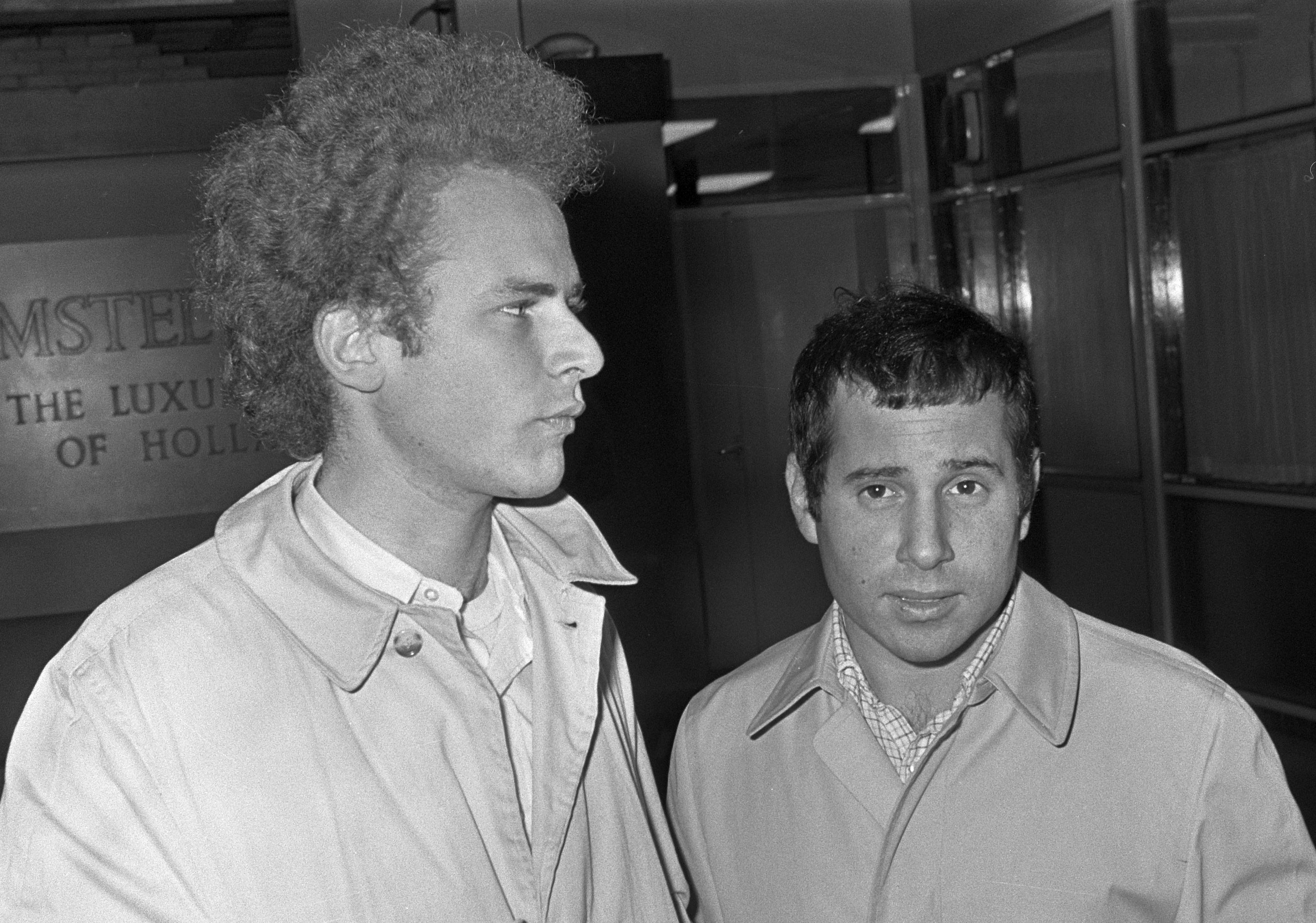

14. Simon & Garfunkel

Simon & Garfunkel are the most famous and culturally pivotal of the many folk combos to emerge from Greenwich Village in the mid-60s. Alongside Bob Dylan, North Jersey-born Paul Simon and Queens-bred Art Garfunkel produced a body of music that remains as symbolically representative of the 1960s as tie-dye and marijuana. Their gorgeously complimentary voices and their neatly articulated observations often transcended the political invective peddled by their fellow scenesters in favor of a more universal folk rock.

Simon and Garfunkel grew up only blocks from one another and attended the same junior high school. In fact, their first performance together was technically in their respective roles during a sixth grade class rendition of Alice in Wonderland. It was as the Everly Brothers-inspired duo Tom & Jerry, however, that they first began writing and recording together in 1956. In spite of a minor regional hit with “Hey Schoolgirl”, followup recordings yielded little traction. The duo split and pursued solo opportunities, with Simon spending some time apprenticing as a songwriter under the tutelage of Carole King and Gerry Goffin.

In 1963, with the folk movement now a dominant force in New York, the two reunited and recorded their debut for Columbia Records. 1964’s “Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.” fared poorly as did the pair’s first set of live shows under the name Simon & Garfunkel. They split once again and Simon traveled to England to commune with British folk scene leaders like Bert Jansch and the future members of Fairport Convention. While Simon was away, a U.S. DJ pulled the majestic “The Sound of Silence” from Wednesday Morning and featured it on his show. Other FM radio stations soon followed suit, prompting producer Tom Wilson to overdub a slightly poppier version of the tune without authorization from the artists.

By the start of 1966, the remixed version of “The Sound of Silence” topped the charts. Once again, it was incumbent upon Simon & Garfunkel to reunite. This time, audiences immediately embraced the acoustic arrangements and aching harmonies on Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme (1966), with songs like “Homeward Bound” establishing Paul Simon as among the period’s most emotive lyricists. In 1967, Simon & Garfunkel provided the music for Mike Nichols’ generational film, The Graduate, resulting in an even higher profile for the rising stars.

This helped to propel 1968’s Bookends into the top spot on the charts when it was released, on the same April 1968 week that Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Against a backdrop of street riots and protests, Bookends became the duo’s biggest hit, anchored by “Mrs. Robinson”, “America”, and “A Hazy Shade of Winter.” Though the lifelong friends were now at the height of their success, they both began to strain at the reins of their partnership. Simon & Garfunkel’s final statement would be perhaps their most musically ambitious as well, with Bridge Over Troubled Water. featuring the grandiose production of the title track and the sweeping “The Boxer.” Bridge would go on to sell roughly 25 million copies, though the duo would be no more.

Simon & Garfunkel have reunited on numerous occasions since their split, most famously for a free Central Park performance in 1981 that attracted 500,000 spectators.

hey were also inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990. Their partnership has been frequently overshadowed by Paul Simon’s substantial and critically important solo output in the decades since, but there are few acts that evoke the storied 1960s with as much grace and yearning as Simon & Garfunkel.

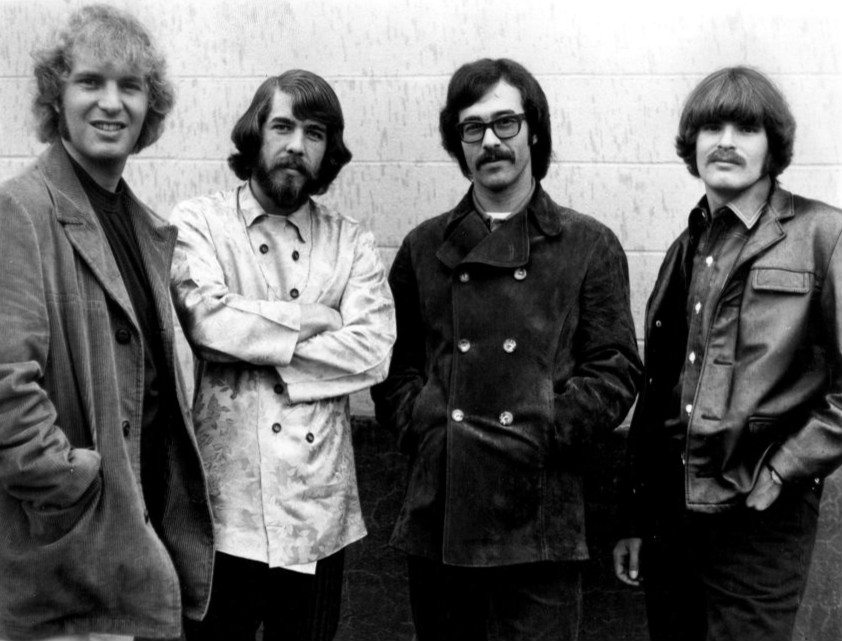

13. Creedence Clearwater Revival

If you ever meet somebody who doesn’t like Creedence Clearwater Revival, be wary. This person may well be a cyborg sent from the future to destroy humanity. There’s really no other explanation. Everybody loves Creedence.

John Fogerty, Stu Cook, and Doug Clifford met in their Bay Area high school as teens and began jamming together after class as well as backing John’s older brother Tom during local gigs.

Originally performing under the name The Blue Velvets and peddling in rock and roll standards, they scored a contract with a jazz label called Fantasy in 1964. Shortly thereafter, John discovered his signature choogling vocal and they took the name The Golliwogs to reflect the swampier garage rock that this seemed to accommodate.

In 1966, with the Vietnam War in full-swing, John and Doug Clifford were drafted into service. Both entered into reserve units but the disruption effectively ended their productivity until 1968. Reunited, they adopted their new name, with “Revival” implying their intensified commitment to the band’s future. Their eponymous debut launched them to immediate success in 1968 with a cover of Dale Hawkins’s “Suzie Q.”

It would also begin a three year run of excellence borne out in a string of perfect full-length records and a consequent flood of FM classics. Creedence created an utterly original backwood bayou sound that was nonetheless brilliantly predisposed to charting success. They were also stunningly prolific during their short lifespan, releasing no fewer than three records in 1969 (Bayou Country; Green River; Willy and the Poor Boys) and headlining Woodstock that summer.

All were hits, yielding some of the finest songs to enter the universal book of rock standards, including one of the era’s more incisive protest songs in “Fortunate Son”, the celebratory jug-band shuffle of “Down On the Corner”, and, in “Proud Mary”, one of the most important American compositions of the 20th Century. After setting the record for most #2 charting records on the Billboard Hot 100, Creedence landed their first #1 with 1970’s Cosmo’s Factory.

By this time, however, tensions between John Fogerty and his bandmates were coming to a head. Fogerty was the band’s singular talent, and made it known to the others by ruling with an iron fist. This, and the increasingly onerous terms of its deal with Fantasy, led to Tom’s departure in 1970 and, after two consequent albums, the dissolution of the band in 1972. Though Tom Fogerty passed away in 1990, Cook and Clifford have toured under the name Creedence Clearwater Revisited while John continues to enjoy success as a solo musician.

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees, purveyors of roughly 26 million records in the U.S., and inventors of the swamp rock genre, CCR made a mighty imprint in their four years on this earth.

Photo By: Fantasy Records – eBay itemphoto frontphoto back, Public Domain

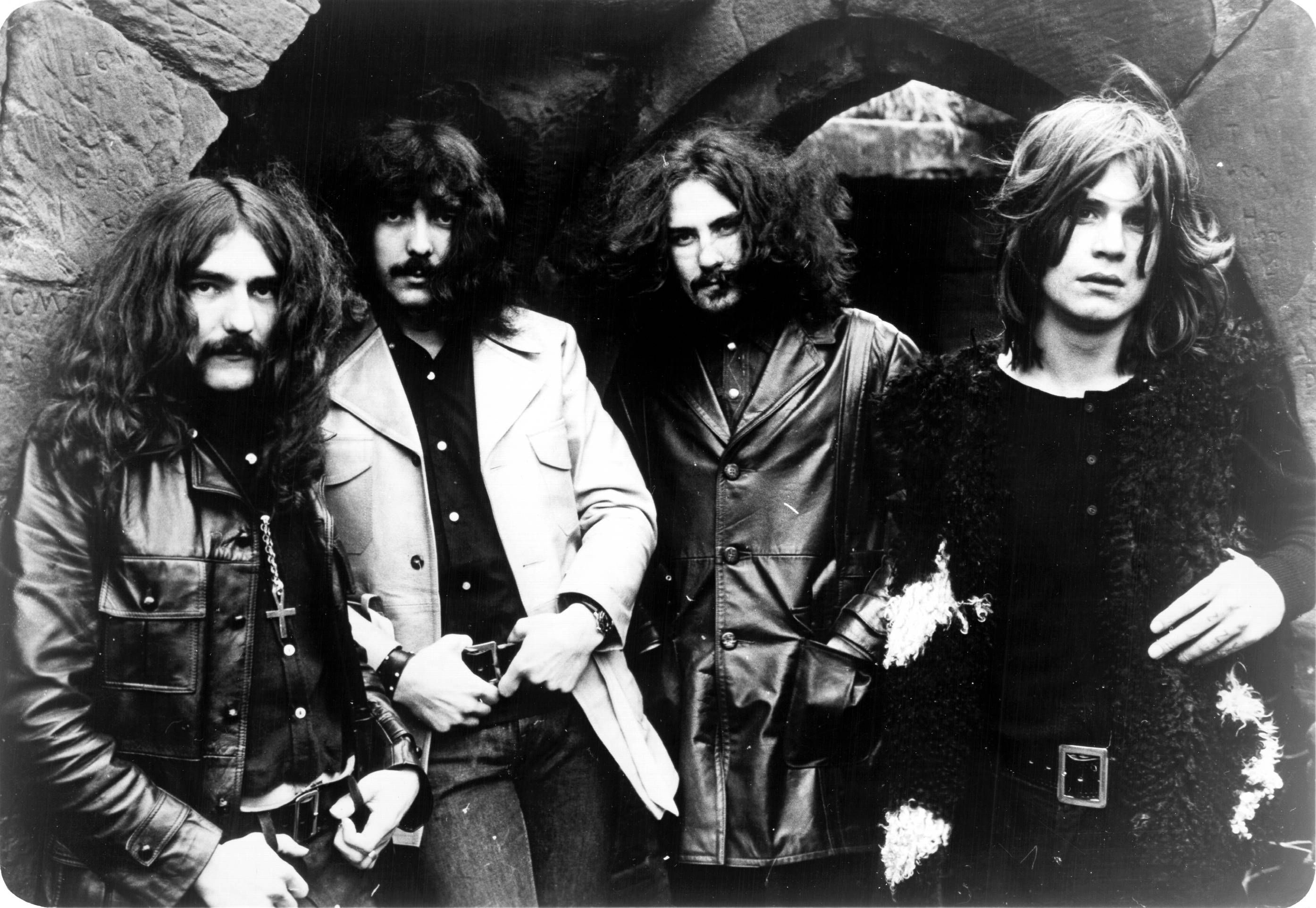

12. Black Sabbath

It’s hard to think of a band that was more critically derided in its time and simultaneously more influential in our time. If the future vision of the world as depicted in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure is true, and heavy metal does indeed lead the way to the enlightenment of civilization, we will have Black Sabbath to thank.

Though the lineup has seen numerous shifts over the band’s 40+ years of operation, its founding four members are the reason for its inclusion here. Birmingham, England musicians Tommy Iommi (guitar), Bill Ward (drums), Geezer Butler (bass), and Ozzy Osbourne (vocals), formed the inauspiciously named Polka Tulk Blues Band in 1968.

Though the band began as a standard heavy blues rock combo, they took a sharp left turn in 1969 after observing that a horror film screening across the street was drawing a larger crowd than was their gig. Employing a musical tritone known as the “Devil’s Interval” for its dark and ominous resonance, the band changed its name to correspond with its first doom-laded composition, “Black Sabbath.”

The band embraced the decidedly low-budget horror conceit in its music and image, most particularly Ozzy Osbourne, whose howling incantations channeled a decidedly necromantic vision. Playing their first gig under this new approach in the summer of ’69, they had a record deal with Philips by that fall. Their self-titled debut dropped appropriately enough, on Friday the 13th, in February of 1970. The permeating gloom and pummeling riffs came in stark contrast to the hippie love-in that dominated rock music in the preceding years.

Critics absolutely hated the album but it rapidly sold a million copies and spent more than a year on America’s Billboard 200 charts. Indeed, it was such a surprise success that the band delayed the release of its followup, Paranoid (1971) so as not to detract from the debut’s continued sales. With Paranoid, Sabbath established the formula that would take it largely through Osbourne’s stint, flanking tight riff rockers like the title track (the band’s only top ten hit), with long, heavy, pyrotechnic jams. Like its predecessor and those that would come immediately thereafter, Paranoid was reviled by critics and gobbled up by a growing metalhead subculture.

The mid-’70s saw the release of an additional four classic LPs—Master of Reality (1971), Vol. 4 (1972), Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (1973), and Sabotage (1975). All but the last would be certified platinum in their first year. Though Sabbath doggedly overcame critical disregard, its growing popularity would also give the band’s members access to all the drugs and alcohol they could consume. They ran with the opportunity, with each album’s sessions more disjointed than the last. The cracks began to show on the two final albums of the decade featuring Osbourne. Though all were pretty far gone at this juncture, Osbourne had become the most deeply dysfunctional. The band’s disintegration was highlighted by a 1978 tour in which its lumbering and dispirited performances were largely upstaged by the energy of young openers, Van Halen.

The band fired Osbourne, who descended deeper into his own addictions before eventually emerging to massive solo success. Sabbath continued its run by recruiting a series of singers, most notable among them Ronnie James Dio (formerly of Rainbow) and Ian Gillian (famously of Deep Purple). Though Black Sabbath remained a successful touring and recording unit among metal enthusiasts, every era since Osbourne’s first departure is essentially a non-classic period.

In 1996, capitalizing on the pale of influence cast by his band, Osbourne founded OzzFest, an annual touring festival featuring the day’s top acts in metal, thrash, hardcore, and all related subgenres. These festivals not only demonstrate how far and wide the shadow of Sabbath’s original works still stretches, but 1997’s affair also served as a forum for the long-awaiting reunion of Osbourne and his fellow founding members.

Today, Sabbath continues to tour intermittently as allowed by the ailing health of its former hard-living members. Not only are Sabbath responsible for moving 70 million records worldwide, but the Rock and Roll Hall of Famers ultimately won over critical consensus in the years since their largely maligned and misunderstood metal burrowed its way up from the depths of hell.

Photo By: Warner Bros. Records – Billboard, page 7, 18 July 1970, Public Domain

11. Velvet Underground

It was once famously said about the Velvet Underground that only 30,000 people bought their earth-shattering first record but that every single one of them went out and started a band the next day. Velvet Underground’s commercial impact was basically nil during its existence but the band’s legacy is inescapable.

Their bold marriage of avant garde predilections and rock and roll song structure produced some of the most provocative and confrontational music in either milieu. Indeed, the artistic bent, risqué bohemian themes, and musical aggression were nothing short of revolutionary, prefiguring nearly every extrapolation of punk, college-radio, hardcore, indie, and alternative music thereafter.

Velvet Underground began as The Primitives, a collaboration between New York guitarist Lou Reed and Welsh-born viola player John Cale, the latter of whom had cut his teeth alongside avant-classical mentor La Monte Young. Adding guitarist Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker (the only female drummer from the ’60s that I can think of), and subsequently becoming acquainted with pop artist and scene-maker Andy Warhol, the group became The Velvet Underground in 1965.

Acting as the group’s manager, Warhol played a significant role in helping the Velvets gain visibility, first by locking them down as the house band for his way-out-there New York Factory parties, and subsequently by employing them as part of a touring art installation called the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. It was in this context that the group developed its early material, drone-laden rockers and tribal funeral dirges about sadomasochism, drug use, cross-dressing and pretty much everything else that flourished around them in the Warhol scene.

Warhol also introduced the band to German chanteuse Nico, whose detached and icy vocals proved the perfect foil to Reed’s deadpan delivery on 1967’s Verve-released Velvet Underground & Nico. Mostly because the jazz label had no idea what to make of it, they had delayed release on the record for nearly a year. When it was finally released, it registered lightly on the bottom of the charts before a dispute over the use of an actor’s image on the back cover resulted in a temporary halt of distribution. The record never recovered from the disruption, in spite of its eye-catching and iconic Warhol-designed banana cover.

Today, this debut is rightly seen as among the most important records ever produced, a challenging collection of songs that careens from the drug-deal rocker “I’m Waiting for the Man”, to the gentle “Sunday Morning”, from the terrifying viola squall of “Heroin” to the chugging acidic energy of “European Son.” So unprecedented was the music on this debut that Verve was more than reluctant to release it, relenting only because of Nico’s already-established reputation.

Whatever the label lacked in vision, they were not wrong from a commercial standpoint. The first record was a flop, as was its followup. White Light/White Heat entered the lowest reaches of the charts before falling out of the bottom. Its even more abrasive, wall-of-feedback approach alienated record buyers but basically laid out the blueprint for future lo-fi heroes like Sonic Youth. Frustrated by their lack of success, Reed and Cale strained to move the band in separate directions. The former favored a more accessible and pop-friendly approach while the latter advocated an even deeper probing of the band’s experimental side.

The fracture led to Cale’s firing in 1968. Replacing him with Doug Yule, Reed assumed unchallenged leadership of the group and directed the band’s final two albums in a far more conventional but no less influential direction. Velvet Underground (1969) was driven by a more delicate approach on lovely bedroom folk like “Candy Says” and “Pale Blue Eyes.” Loaded (1970), recorded with the understanding that Reed would shortly be departing for a solo career, was a straight-ahead rock record.

In spite of containing two of the band’s most popular songs in “Sweet Jane” and “Rock and Roll”, the highly listenable Loaded was deprived promotional support. With Reed departed, Velvet Underground’s original lineup disbanded, essentially leaving latter-day recruit Doug Yule holding the bag. He pushed on for a relatively pointless three years before calling it a day.

Both John Cale and Lou Reed, the latter of whom passed away in 2013, went on to enjoy compelling and provocative solo careers. Reed would earn two entries into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for his own work and for his world-changing role as the leader of the Velvet Underground.

10. Queen

Rock and roll explored its most flamboyant, androgynous and theatrical impulses in the 1970s. Perhaps the nexus point of these impulses is Queen, a group begun in the late ’60s as a London Imperial College combo called Smile. When the group’s bassist departed, guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor recruited Zanzibar-born singer Farrokh Bulsara (better known to you as Freddie Mercury). Adding bassist John Deacon, Queen saw success in the U.K. from the start.

Their first two records, released in 1973 and 1974, received mixed reviews from the day’s critics for what many characterized as a tacky and overproduced attempt to merge heavy metal and classical music. It was their third record, 1974’s Sheer Heart Attack that would deliver Queen to international success on a raft of hard riffs and vaudevillian camp.

The picture-perfect single “Killer Queen” reflected Queen’s theretofore unknown capacity for tastefully rendered theatre-pop. It reached #2 in England and earned Queen a #12 hit in the U.S.

Queen followed with a series of classic full-length concept records, perfecting its unique paradox of fey humor and guitar-rock machismo. A Night at the Opera (1975), A Day at the Races (1976), and News of the World (1977), established Queen as among the decade’s most omnipresent radio-play and stadium-touring bands. Mercury’s status as a singularly commanding frontman grew as the band circled the world.

If the Who invented the rock opera, it was during this stage that Queen invented Opera Rock, a hybrid of hard rock, progressive instrumentation, musical theatre arrangements, choral flourishes, British chamber music, and explicit references to landmark classical pieces. “Bohemian Rhapsody”, off of Night at the Opera, is the most fully realized concentration of these elements and would become the band’s most important composition. Derided by some critics for its bombast, which made it the most expensively produced single in history to that date, “Bohemian Rhapsody” would hit #1 in the U.K. and #9 in the U.S.

By the approach of the late ’70s, Queen was trading its more theatrical leanings for straight-ahead pop fare. With the oft-sampled “Another One Bites the Dust”, and the rockabilly inflected “Crazy Little Thing Called Love”, Queen and Mercury proved impossible to pigeonhole and equally as impossible to keep from the charts. It also bears noting that this era’s “We Are the Champions/We Will Rock You” may be the single most frequently played song in the history of soccer stadiums.

At the height of their popularity, Freddie Mercury suddenly disembarked from the band to produce a largely unsuccessful solo record. But the band’s reunion in 1985 would make history. Queen’s 21-minute set at Wembley’s Stadium as part of the Live Aid mega-concert is widely seen as one of the greatest live performances by any rock band, ever. In fact, it topped an industry poll indicating as much in 2005. The acclaim that followed this performance led to a world-conquering year-long tour, culminating in a sold-out performance at the famous Knebworth House in Hertfordshire before a massive throng of 120,000+ fans on August 9th, 1986. Sadly, this would be Freddie’s final performance.

When Freddie Mercury died of AIDS in 1991, it shocked the world. Few were even aware that the secretive frontman had been ill. As a testament to the band’s lasting influence, “Bohemian Rhapsody” returned to #1 on the British charts at the time of his passing. It hit #2 once again on the American charts the following year after being memorably featured in the movie Wayne’s World.

Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2001, Queen has moved somewhere between 200 and 300 million units worldwide. Since Mercury’s passing, the band’s surviving members have toured behind Bad Company singer Paul Rodgers and former American Idol standout Adam Lambert.

Photo By: Carl Lender, CC BY-SA 3.0

9. The Who

50 years ago, Roger Daltrey famously sang that he hoped to die before he got old. Boy, would he live to regret that statement, or what?

Well into his 70s, Daltrey and his musical foil, Pete Townshend, continue to record and tour when the mood strikes them. Along with bassist John Entwistle and drummer Keith Moon, the group began performing as The Who in 1964.

They distinguished themselves from their blues-obsessed peers like the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds by instead probing American soul and R&B in their earliest sets. Combined with their distinctively mod appeal, the lean and loud quartet would also prove one of rock’s most ambitious and accomplished combos in the coming decades.

From the start, the Who attracted audiences with its penchant for punctuating performances by smashing its equipment to bits. Given how expensive such a performance habit could be, it’s fortunate that the Who gained success relatively quickly. It also helped that Townshend immediately proved himself a clever songwriter. “I Can’t Explain” earned the group a Decca release, which ultimately became popular on Britain’s famous pirate station, Radio Caroline.

It was the group’s 1965 release “My Generation” however, that made The Who famous. Reaching #2 on the U.K. charts, the speed-addled vocal stutter, the menacing bass solo, and the song’s anthemic declaration immediately inserted the Who into the thick of a British Invasion already underway. As the Who played on increasingly larger stages, they’re songwriting became ever-more sophisticated, moving from mod classics like “The Kids Are Alright” to the multi-part suite “A Quick One While He’s Away” in a matter of two years.

By 1967, the Who had also firmly established its reputation for destructive live performances, backstage scuffling, and chemical appetites, most especially that of nutbar drummer Keith Moon. It was this same year that the Who made its American debut at the Monterey Pop Festival. Though their violent antics were not entirely in-step with America’s raging hippie revolution, their next move would endear them to the free love generation. Pete Townshend’s songwriting vision was growing in scope, a fact realized on 1969’s Tommy. The so-called ‘rock opera’ offered listeners a musical narrative about a “deaf, dumb and blind boy” who excels at pinball and goes on to become a religious demagogue.

In addition to substantially expanding notions about what could be done either within the LP medium or the rock milieu, Tommy became the centerpiece of Who performances for the next two years, including gigs at Woodstock and the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival. Both are considered career-expanding performances, and would help Tommy ultimately sell 20 million copies while spawning countless Broadway adaptations and a campy but rock-star laden 1975 film.

In the coming decade, the Who would dive headlong into its swelling fame, as well as into the harder, louder rock tendencies that were increasingly in fashion. As rock music moved from clubs and dive bars into arenas and stadiums, the Who proved more than equal to the task. This transition was significantly aided by the 1971 release of “Who’s Next”, a classic rock record par excellence. Providing the Who with perennial concert centerpieces in “Baba O’Riley”, “Won’t Get Fooled Again”, and “Bargain”, Who’s Next would go on to receive triple platinum certification.

Over the course of the ’70s, the Who embraced their role as stadium rockers with big, blustery tunes like “Who Are You” and “Eminence Front.” But Keith Moon’s behavior became increasingly legendary, and not in a good way. The ever-excellent drummer was also declining deeper into alcoholism, a habit which worsened considerably when he accidentally ran over and killed his chauffeur and best friend Neil Boland during a fan-fueled melee in 1970. In 1978, ironically after completing alcohol rehabilitation, Moon overdosed on his detox medication.

With Moon’s death, their classic period was over. The Who pushed on for another few years with Small Faces drummer Kenney Jones at the kit. With the exception of a 1989 reunion tour, the Who was largely on hiatus between 1982 and 1996. In the intervening time, they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and, even in spite of bassist John Entwistle’s death in 2002, verily refuse to stop touring.

Who can blame them, with more than 100 million records moved, these septuagenarians still sell out stadiums? Not bad for a few geezers who planned on being dead by now.

Photo By: Jim Summaria – Contact us/Photo submission, CC BY-SA 3.0

8. Bob Marley & The Wailers

No entity did more to proliferate Jamaican music than Bob Marley & The Wailers. Owing to a background steeped heavily in American R&B and soul, the Wailers would create their own highly spiritual, deeply moving, and readily accessible brand of reggae.

Their sound would, in turn, transform the reggae genre, and alter the course of western popular music, the latter of which absorbed reggae’s loping rhythms and dub production techniques into its own melting pot tradition. Though the Wailers are best known for their charismatic and highly mythologized frontman, their roster is filled with reggae luminaries.

Indeed, the band’s roots begin in 1963, when Trenchtown teenagers Peter Tosh (keyboard), Bunny Wailer (drums), and Bob Marley began playing together as the Wailers. Late that year, the group recorded an anti-violence plea called “Simmer Down”, backed by The Skatalites. The result was a #1 hit in Jamaica.

Still, for a brief time in the mid-’60s, the Wailers’ career would be sidelined by Bob’s marriage and a relocation to Wilmington, Delaware. Though Marley worked unhappily on a Chrysler assembly line, the short stay would not be without value. Marley’s more direct exposure to American soul music would forever color his musical approach. Upon his return to Jamaica, Marley added his wife Rita on backup vocals and reconvened with his old mates.

Soul Rebels, produced by studio visionary Lee “Scratch” Perry, would be the first Wailers record released outside of Jamaica. The group’s rising profile on the island would also give Marley a chance to tour alongside American R&B hitmaker Johnny Nash. It was during their 1972 visit to the U.K. that Marley helped bring reggae to a far wider audience than had previously seen it. Audiences embraced Marley, thus securing the Wailers a contract with Island Records.

Adding the Barrett brothers, Aston (bass) and Carlton (drums), the Wailers entered into a period of stunning progress, with Burnin’ (1973) and Catch a Fire (1973) elevating the prominence and expansiveness of the reggae genre. Songs like “Concrete Jungle”, and “Get Up, Stand Up” helped to establish the Wailers, and Marley in particular, as philosophical and spiritual leaders of their nation. Marley’s adoption of the Rastafarian way of life contributed to a pronounced ideological pacifism, not to mention his well-known penchant for sacramental marijuana.

In 1974, Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh would depart for their respective solo careers, leading to an important change in direction. As Marley’s international star grew, his music turned toward the market. Changing their name to Bob Marley & the Wailers, the group released Natty Dread and with it, reached #92 on the American charts.

As Marley’s fame continued to grow, so too did his political involvement. Two days prior to a planned 1976 appearance at a unity rally designed to bring peace between two warring Jamaican factions, Marley and several of his bandmates were wounded in an attack by armed gunmen. Famously, the Wailers were not deterred from their performance, owing largely to Marley’s unshakable commitment to peace.

It did, however, lead to a two-and-a-half year self-imposed exile to the U.K., where the Wailers subsequently recorded Exodus (1977) and Kaya (1978). With singles “Jamming”, “Waiting in Vain”, and the omnipresent “One Love”, Bob Marley had become a superstar in Britain. Suddenly, every punk and new wave band in the land was working up its own take on Jamaican music (see The Police, The Clash, Madness, The Specials, etc. etc.)

Marley would eventually return to Jamaica, but he would do so with ailing health. Though he had been given a diagnosis of melanoma for a growth on one of his toes, his religious beliefs prevented him from allowing amputation. As a result, Marley’s cancer slowly gathered over three years while his fame grew to even greater heights. He had become a national hero in his home country and one of the world’s most electrifying live performers. He also worked tirelessly, often well past the point of physical exhaustion, aggressively touring the U.S. in support of Uprising (1980)—anchored by the aching “Redemption Song” and the #5 U.K. hit, “Could You Be Loved?”.

In May of 1981, Marley succumbed to his illness while flying between Germany and Jamaica. He was given a statesman’s burial, with Prime Minister Edward Seaga delivering his final eulogy. With 75 million records sold, Bob Marley & the Wailers are by far the most successful reggae group in history. Marley was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994.

Photo By: Tankfield – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

7. Nirvana

Nirvana’s success so profoundly changed the course of popular music that it’s easy to forget just how brief the period of their fame was. Their debut album dropped in the summer of 1991. By the spring of 1994, we were mourning the band’s death.

But Nirvana’s colossal and unexpected success helped to make the world of popular music increasingly safe for the strange, wonderful, and wild sounds of the ’90s alternative boom. Typically lumped under the grunge sobriquet, Nirvana was actually a punk-pop band, centered around a frontman whose charisma was largely inextricable from his misery.

Nirvana began in 1987 when high school friends Kurt Cobain and Krist Novoselic began playing together in the area around their native Aberdeen, Washington. Influenced by hardcore punk icons like the Melvins and the Butthole Surfers, the two (along with a drummer named Chad Channing), recorded a 1989 debut called Bleach on the highly influential indie rock label, Sub Pop. The album made Nirvana an underground sensation, demonstrating an uncommon sense of melody for a hardcore band. Finding itself at the center of major label attention, Nirvana replaced Channing with the powerful Dave Grohl and recorded Nevermind for Geffen in 1991.