From The Yardbirds to White Stripes, from The Pixies to The Impressions, here’s another 25 of the 100 greatest Rock bands of all time (numbers 75–51).

If you’re new here, be sure to check out the series introduction where I lay out what qualifies a band for inclusion on this list (be a band; be excellent; be successful; or be influential). I also describe my unavoidably personal ranking methodology and explain why I include rap, soul, and vocal groups in a list of “rock bands.”

If you’ve already read all of that stuff, jump right to the list.

See Who Makes the List…

What is Rock?

Simply stated, Rock Music formed the basic DNA of popular music from about 1960 to 2000.

The 1950s are fondly remembered as The Golden Age of Rock and Roll. Much of what we would call Rock and Roll—Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, etc.—is firmly rooted in the blues, gospel, country, and R&B which came before it. But when these sounds merged—and most importantly, when the line separating Black and white music blurred—the cultural phenomenon known as rock and roll engulfed America’s youth.

Then, in 1959, a series of unfortunate events signaled an end to this era, including Elvis Presley’s draft into military service, Little Richard’s departure into the priesthood, and the tragic airplane crash that claimed the lives of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper.

Rock and Roll had reached its first low ebb, leaving popular music in the well-manicured hands of treacly teen idols like Frankie Avalon and Fabian. Rock and Roll had many critics, including an outspoken contingent of segregationists who decried the spread of so-called “jungle music.” Those who thought of rock and roll as coarse, vulgar, and little more than a teen-fueled fad were vindicated. Rock and roll was dead.

Then the Beatles and Stones washed ashore in 1964. A year later, Bob Dylan plugged his guitar into an amp at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival; Motown beamed the Detroit sound into every dancefloor in America; Brian Wilson took the Beach Boys into unchartered waters; the Grateful Dead tried LSD for the first time; and Bruce Spingsteen’s mother took out a loan to buy her kid his first guitar.

Rock and Roll was reborn, but with a harder edge, a more adventurous spirit, and substantially longer hair. It was in this moment that Rock and Roll became “rock”—something less formulaic, less immediately definable, and far more expansive. It became something more than some guitars and a drum kit. Rock became a palette of infinite colors inspiring boldness, experimentation, and the total deconstruction of barriers.

Rock is the catch-all terminology for everything that came after the first Golden Age—British Invasion, Girl Groups, Motown, Greenwich Village, Psychedelia, Progressive Rock, Soul, R&B, Metal, Punk, New Wave, Disco, Funk, Hip Hop, Alternative, and even Rock and Roll. So when we call something a “rock band,” let’s try to avoid any hangups about what we think ‘rock’ should sound like. Avoiding exactly those kinds of preconceived notions is what helped the artists on this list to earn our esteemed recognition, not to mention many lesser honors like unspeakable wealth and enshrinement in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Ok. You get the point. Rock is everything. Everything is rock.

Qualifications For Inclusion

- Be a Band

First, in order to be considered one of the 100 Best Rock Bands of All Time, one must be a band. Any group of people who play instruments, write songs, and perform concerts together qualifies as a band. Sooooo, for instance, Hootie & the Blowfish would qualify as a band. Wait. Come back. That’s just an example. They’re not on the list. Also qualifying for inclusion here are duos, vocal combos, rap crews, house bands, and whatever you’d call the colorful mass of humans that comprise Parliament/Funkadelic. Not eligible for inclusion are solo artists, which explains the conspicuous absence of Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and Rick Astley.

- Be Born After 1955

Also not eligible are bands whose output generally predates the proliferation of rock and roll. R&B groups like Billy Ward and his Dominos and vocal combos like the Ink Spots have an unquestionable place of importance in the early development of rock and roll. But there is an invisible line in history that bisects at the point where Elvis Presley first came to national prominence in 1955. Thus, only those who achieved their greatest musical accomplishments thereafter may be considered.

- Be Excellent;

Of course, everything I just said does nothing to prevent Hootie & the Blowfish from making the list. This is why our next qualification is critical. The top qualification for inclusion here is musical, instrumental, and/or artistic excellence. Bands included here helped raise the standards of songcraft, live performance, studio ingenuity, or virtuosity. Sometimes, artistic excellence is universal enough to transcend subjectivity. For instance, if you make a Top 100 list that doesn’t include Pink Floyd, it must be because Roger Waters ran over your dog. Otherwise, the consensus is that they were pretty darn excellent. The same is true of nearly all the artists included here.

- Or Be Successful;

I admit that not every band on this list is inherently excellent. But some bands are simply too successful to miss the cut. Some bands sold so many records that, no matter what you or I think of them, neither of us could deny their impact on popular culture. Yes, the Eagles are on this list. Yes, I recognize that they could be insufferably smug. But really, there’s just no way a band could sell 150 million records without doing a lot of things really right.

- Or Be Influential

Some artists on the list may defy any conventional definition of excellence or success, but must be ranked for the cultural impact of their work. Sid Vicious was such a crummy musician that his fellow Sex Pistols would famously turn down the volume on his amp during live performances. But the depraved bassist also perfectly embodied the nihilism and rage that made his band monumentally influential. In order to be included on this list, being excellent helps. But if you don’t have that, making an earth-shattering impression on the course of history is the next best thing.

Ranking

Our ranking procedure was extremely scientific in that I wore a lab coat and safety goggles.

Consistent with our broader mission here at Music Influence, the goal was to rank artists by influence. When we rank one artist above another, we are not making the argument that the former artist is better than the latter. Instead, we’re arguing that the higher-ranking artist is more influential. Thus, when we place hip hop pioneers Run D.M.C. ahead of alt-radio godfathers R.E.M., we are not arguing that Run D.M.C. is better. Instead, we are claiming that the Hollis, Queens trio did just slightly more to change the face of popular music than did the quartet out of Athens, Georgia.

That said, unlike other rankings on our site, this list isn’t powered by our algorithm. Instead, influence is informed by a set of unweighted variables including commercial success, artistic importance, cultural relevance, and personal preference. Yeah, that’s right, there’s some bias in here. If you don’t like it, write your own list. Seriously. I’m not being pithy. It’s a really fun exercise and I wish you the best.

But this is my list so you’re bound to disagree with some of my choices. You probably think I’m crazy to rank this band over that band. You might think I’m an idiot for ranking a band you hate ten spots above a band that you’d sell a kidney (perhaps even your own) to see live. You might wish to send me hate mail for failing to find the space in 100 entries and 50,000+ words to even mention the band that you’ve dedicated your adult life to worshiping. (Rush fans—please direct your Dr. Who-reference-riddled diatribes directly to our webmaster).

Well that’s the beauty of a list like this. There’s no way it’s going to be 100% right but you can’t prove it’s wrong. This means we get to have a fantastic and impossible-to-settle debate about rock music, about what it is, where it’s been, and where it’s going.

Enough introducing. Let’s get right into the bands.

The Best Rock Bands of All Time: 75-51

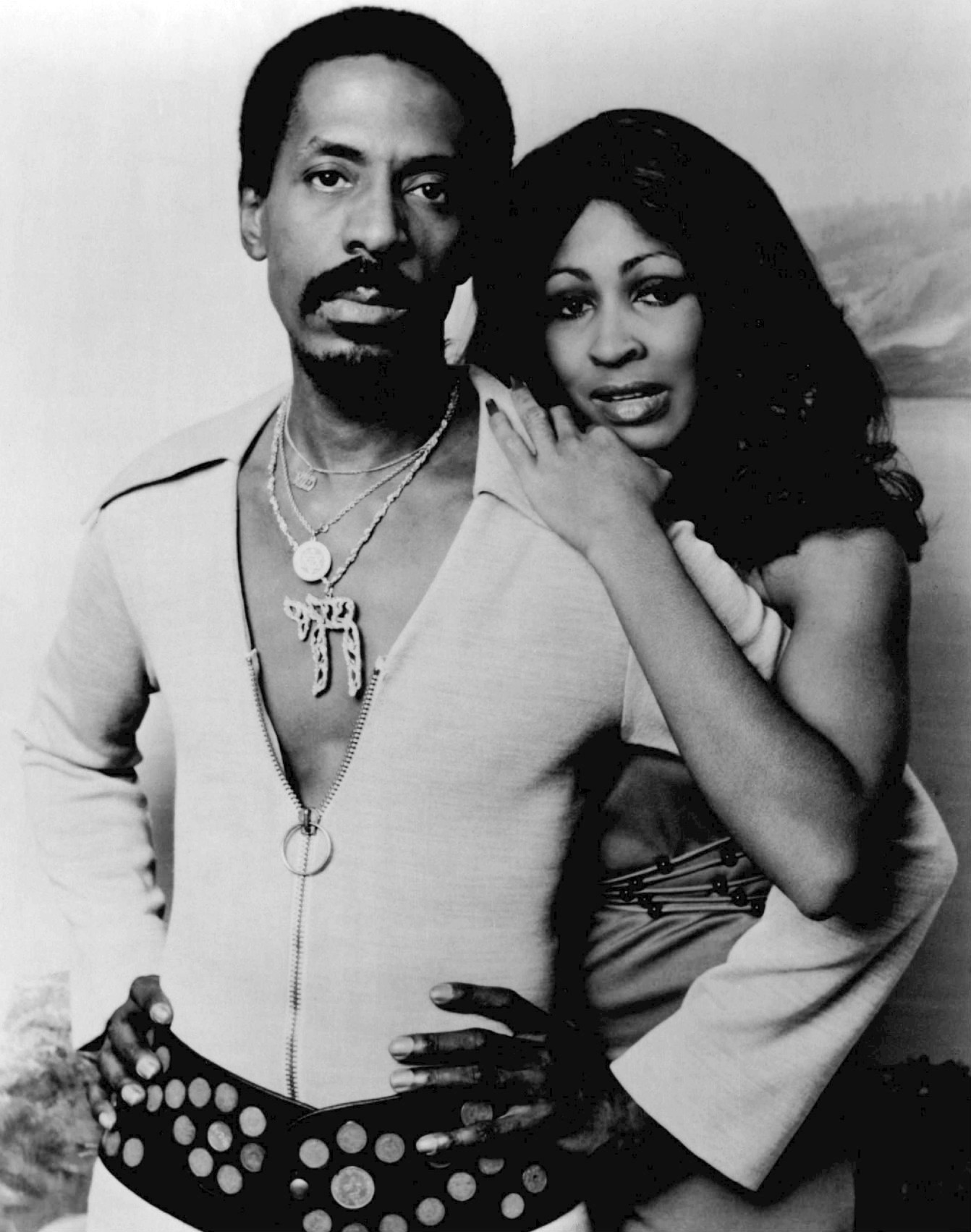

75. Ike & Tina Turner

Between 1960 and 1976, there was no hotter or more explosive show in R&B than the Ike & Tina Turner revue. When the two first met in the late 1950s, Ike was already a star and Tina, a star-struck young girl. But over time, the two musicians would see a reversal of roles. The powerful vocalist would come to overshadow her husband even as he attempted to control every aspect of her life. Indeed, evidence suggests that the abusive and unpredictable Ike Turner was not a particularly nice man. But he did discover the Tennessee-born Anna Mae Bullock (A.K.A. “Tina Turner”) and he did fix her to her future stage name. For that alone, his importance in rock and roll history is assured.

It was, however, Tina Turner’s own inimitable musical authority that would place her among the most magnetic performers in rock history. Her amazing longevity, throttling performances, and sustained draw as a live act have earned Turner her title as The Queen of Rock ‘n Roll.

Young Anna’s first performances were at her family’s Baptist church but she harbored few expectations of ever becoming a professional musician. She was a cheerleader and a basketball player in high school, and, following a transfer to the St. Louis area, graduated from Sumner High School in 1958 with plans of becoming a nurse.

While working as a nurse’s aid, she and her sister became regulars in the city’s vibrant nightclub scene. Among this scene’s most popular acts was Ike Turner’s Kings of Rhythm. Turner’s band had already laid claim to the unique distinction of recording, in 1951, what many historians identify as the very first Rock and Roll song, “Rocket 88,” under the name Jackie Brenston and His Delta Cats.

Anna was transfixed by Turner and introduced herself during intermission. He cajoled her to take the microphone and, after a single performance, invited her to join the band. She almost immediately became its primary attraction.

Through the early 60s, Tina’s husky vocals, provocative dancing, and commanding stage presence made Ike & Tina a premier touring act. Tina gave Ike’s seasoned combo a sexy, explosive, even dangerous quality that helped the act rise above its peers on the chitlin’ circuit. Ike and Tina also entered into a romantic relationship, though it was one famously marked by psychological and physical violence.

When they partnered with Wall of Sound impresario Phil Spector (speaking of psychological and physical violence) in 1965, Ike and Tina began a run at the charts with iconic performances like “River Deep-Mountain High,” (1966), “Proud Mary” (1971), and the autobiographical “Nutbush City Limits” (1973). Turner also contributed a memorable performance as The Acid Queen in the Who’s 1975 film adaptation of their rock opera, Tommy.

The following year, Tina filed for divorce from Ike and, upon winning her freedom, began her solo career. Though chart success was scarce in the late 70s and during the turn of the decade, she remained a knockout in live performances. Then, in 1984, she released the record Private Dancer, launching a Top Ten hit with “What’s Love Got To Do With It” and earning her greatest success as an artist yet. The album earned her four Grammys that year and set her on a course for a fertile decade both in the studio and as a touring act.

Ike Turner would while away his latter years struggling with a crack/cocaine addiction before succumbing to an overdose in 2007. In spite of his role as a key architect of rock and roll, the verily unlikable Ike Turner is rarely held in the same esteem as his Golden Age contemporaries. By drastic contrast, Tina Turner is a Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, a winner of eight Grammys, owner of a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and by some accounts, has sold more concert tickets than any solo artist in history.

Tina Turner’s passing, at age 83 in May of 2023, was met with an outpouring of love and adulation.

Photo By: United Artists Records-publicity release by McFadden, Strauss, Irwin. – eBayfrontback, Public Domain

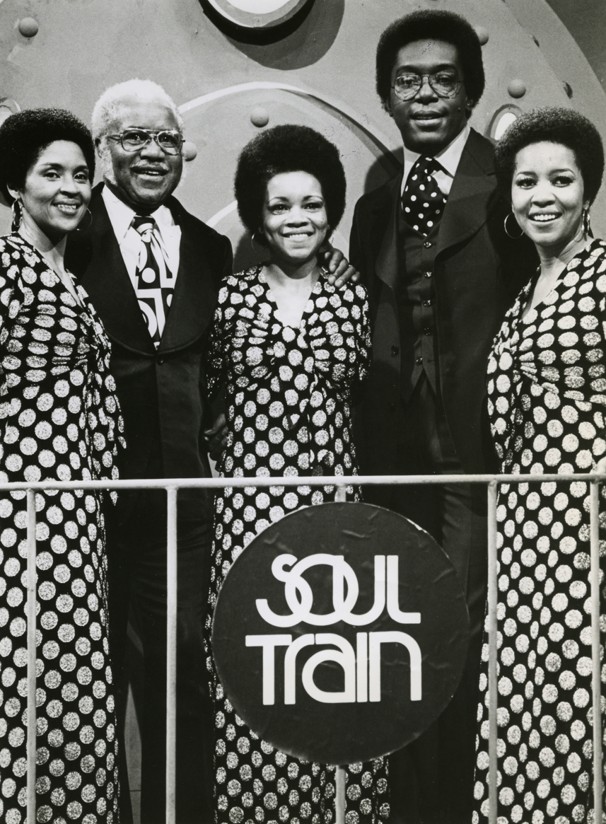

74. The Staple Singers

Many a famous singer made the jump to stardom from the church. Gospel music was so often the source material for the vocal harmonies, soul shakers, and R&B anthems that filtered into secular music. Few if any artists, however, remained as deeply committed to gospel as did the Staple Singers while achieving so much within the context of popular music. The family group’s soaring harmonies and themes of self-empowerment gained cultural importance in the period immediately following the Civil Rights era.

The Staple Singers were led by patriarch Roebuck Pops Staples, whose sonorous and reverb-drenched guitar-playing would become a substantial influence on future blues and soul rockers. Relocating from Mississippi to Chicago in search of labor like so many other young Black men in the 1940s, Staples’ music career began when he appeared in his brother’s church alongside daughters Cleotha, Pervis, and Mavis. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Staple Singers moved through a bevy of labels to produce best-selling R&B charters, including “Uncloudy Day” and their take on the Carter Family standard “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.”

In addition to Pops Staples’ distinctive guitar tone, Mavis Staples emerged as a star for her powerful pipes. As the Civil Rights movement intensified, the Staple Singers turned their attention increasingly from spiritual themes to the very concrete themes of Black pride and equality. A partnership with the legendary Memphis soul label, Stax, led the Staple Singers to their biggest and most important recordings.

With 1971’s “Respect Yourself” and “I’ll Take You There,” the Staple Singers made themselves a leading voice of optimism after the revolutionary tumult of the 1960s. The former hit #12 on the Billboard Hot 100 and the latter struck #1. With the decline of Stax, the Staples moved over to Curtom (Curtis Mayfield’s label) and cut a final #1 with “Let’s Do It Again.”

Ensuing years would find the Staples increasingly well-regarded for their impact on popular music and their contributions to the improving racial dialogue of the 1970s. Their role earned them passage into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1999, just a year before Pops Staples passed on. Cleotha is also deceased. Mavis continues to tour, perform, and record, generally enjoying well-earned adulation for everything she does.

73. The Yardbirds

The Yardbirds boasted not one, not two, but three of the greatest players ever to wield the guitar. Forever the answer to one of rock’s most mind-boggling trivia questions, the Yardbirds launched the careers of Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page. That would be good enough for the place they hold in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Fortunately, there’s more to it than that. These musicians didn’t just cut their teeth before moving on to greater fame. While within, the members of the Yardbirds created a hypercharged London blues as tense, nervy, and manic as any produced during the Beat Boom. Subsequently, the Yardbirds pursued a psychedelic vision that would pave the way musically and organizationally for the founding of Led Zeppelin.

The Yardbirds began in 1963 around primary songwriter and bassist Paul Samwell-Smith, Keith Relf (vocals, harmonica), Jim McCarty (drums), Chris Dreja (guitar), and Top Topham (guitar). As the band’s first lead guitarist, Topham may be one of the most forgotten footnotes in history. He was replaced by self-declared blues purist and virtuoso Eric Clapton before the group scored a coveted residency at the Crawdaddy Club. Stepping into the lurch as the previous house band, the Rolling Stones, moved on to superstardom, the Yardbirds immediately attracted their own following.

The Yardbirds made the unusual decision of releasing a live performance from the Marquee Club as their debut. 1964’s Five Live Yardbirds would prove a perfect showcase for the band’s uncommon instrumental prowess.

Their approach to the blues was slightly more anarchic than that of contemporaries like the Stones. Most of their tunes crescendoed in chaotic, high-tempo “rave-ups.” These trademark rave-ups were an early forerunner to the wild improvisation that would dominate rock music by the end of the decade. While much of their early work consisted of Chuck Berry and Sonny Boy Williamson covers, it was the professionally-written “For Your Love” that placed the Yardbirds in the thick of a rising British pop tide.

Though it would sell a million couples, it would also clash with Clapton’s interest in the blues. The group’s already-revered guitarist left for John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. Two days later, an experimental shredder from a group called the Tridents was on stage with the Yardbirds. Jeff Beck brought a far more adventurous philosophy to the band, the influence of which immediately bled into its songwriting and studio work.

With Beck, the Yardbirds played more liberally with techniques like feedback and distortion while releasing a decidedly trippier set of originals in “Heart Full of Soul,” “Shapes of Things,” and the psych-Mod mindbender, “Over Under Sideways Down.” By 1966, the group had also issued its most important studio record with Roger the Engineer.

Midway through 1966, Samwell-Smith departed the group to begin his career as a producer. This would prompt Beck to invite his friend Jimmy Page onboard. The brief overlapping of these guitarists would create a tantalizing musical prospect, perhaps only fully realized on the vaguely Gregorian psychedelic nugget, “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago.”

Unfortunately, this exciting lineup would never be realized on a full studio record. During that year’s U.S. tour, Beck’s temper and tardiness resulted in his termination. Page assumed leadership duties for the Yardbirds. Without the group’s primary songwriter (in Samwell-Smith), the Yardbirds lost direction and chart momentum. The most significant thing to come out of this era was the development of both the approach and material that would soon become Zeppelin’s. Page worked up his versions of Jake Holmes’ “Dazed and Confused,” and Tiny Bradshaw’s “The Train Kept Rollin” in live performances even as the band decayed around him.

As bandmate Keith Relf took an interest in folkier pursuits (later realized by his membership in the minstrelsy prog outfit, Renaissance), Page’s growing interest in heavier rock led to the group’s dissolution. Page led one tour of a group that he called the New Yardbirds, largely to fulfill contractual obligations, before taking the name Led Zeppelin and looming enormously over popular music.

In spite of the modest scope of their official output, the Yardbirds earned their rightful spot in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992.

Photo By: Wikipedia Photo

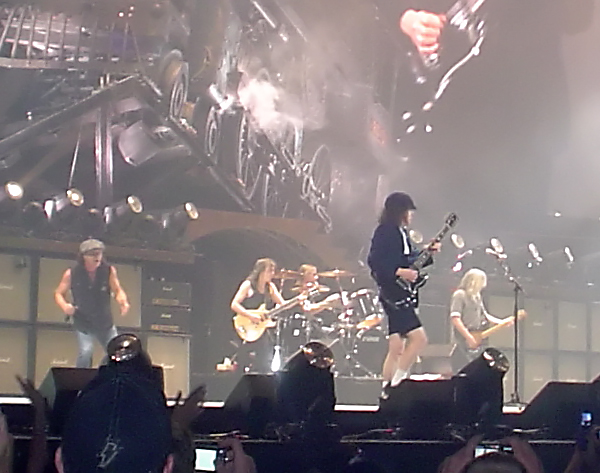

72. AC/DC

AC/DC does one thing but they do it really freaking well. Give these guys credit for never once compromising their vision. This unit is the embodiment of hard rock. Big riffs. Gut-punch vocals. Caveman lyrics. It might sound sophomoric. And quite frankly, it really really is. But once AC/DC had concocted the perfect hard rock formula, they were smart enough to stick with it. Across more than 40 years of tumult and personnel change, AC/DC remained steadfastly committed to its approach, which, it bears noting, is as subtle as a chainsaw.

Brothers George, Malcolm, and Angus Young were born in Glasgow, Scotland but emigrated to Australia in 1963. It was there that George, the eldest of the three, joined the Easybeats and, in 1966, notched the very first internationally charting hit of Aussie origin with “Friday On My Mind.” But far greater success awaited his guitar-slinging younger brothers. Designating George as their manager, AC/DC formed in 1973 and, with lead singer Dave Evans, assimilated into the glam scene exploding around them.

Assuming leadership of the unit, Angus ditched the makeup in favor of his trademark kilt. He also ditched Evans in favor of Bon Scott and the group released its debut album, High Voltage, in 1975. The Australia-only release made the band an immediate success in its home country and a regular feature on its popular Countdown television show. By 1976, this success earned AC/DC opening slots for bands like KISS and Blue Oyster Cult.

Then, in 1978, they released Highway to Hell, whose title track catapulted them into the headlining slot. Their albums and performances were anchored by Angus Young’s massive guitar riffs, the guttural yowling of Bon Scott, and the band’s unabashed objectification of the fairer sex. Also not to be overlooked, Angus Young has rarely if ever performed without bareass mooning his audience.

Before you cry cultural foul on these dinosaurs—who for decades toured with a well-traveled, building-sized inflatable doll named Rosie — you should at least thank them for never recording a power ballad. Instead, with the onset of the 1980s and the hair-metal epidemic, AC/DC doubled down. Bon Scott choked to death on his own vomit, paving the way for the cappie-sporting Brian Johnson, who succeeded remarkably at sounding almost exactly like his predecessor.

With Johnson at the mic, AC/DC recorded 1980’s seminal Back in Black. While the likes of Def Leppard and Motley Crue were polishing the jagged edges off of hard rock, Young and company electrified the genre. Back in Black took the band to a height of success that remains unmatched not only among hard rockers but pretty much everybody else too. Certified 25x platinum in 2019, with more than 50 million units sold worldwide, Back in Black is, by some accounts, the 2nd highest selling album of all-time. Only Michael Jackson’s Thriller is said to have sold more copies.

All told, these Rock and Roll Hall of Famers are among the most successful touring and recording acts of all-time, moving more than 200 million units worldwide.

Photo By: Imhavingfun42 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

71. The Shirelles

By most accounts, the Shirelles were the very first and prototypical of the so-called girl groups, establishing the mold for the female vocal harmony groups that would absolutely dominate the charts in the early and mid-60s. Formed in 1957 by Passaic, New Jersey high school classmates Shirley Owens, Doris Coley, Micki Harris and Beverly Lee, the Shirelles are generally regarded as a self-styled breakthrough act in an era before Black women regularly occupied, let alone dominated, the charts.

The Shirelles’ teenager-in-love themes and their innocent harmonies brought them minor success at first with the mid-level 1958 Decca Records release “I Met Him On a Sunday.” True success was two years off, however. As a flagship signing for the newly formed Scepter Records, the Shirelles released “Tonight’s the Night” and “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow.” The latter, penned by husband and wife songwriting team Carole King and Gerry Goffin, would not only be the first #1 for the Shirelles. It would be the first #1 for a Black female combo and the first chart-topper for any girl-group.

In addition to facilitating a three-year chart run that included subsequent classics “Mama Said” and “Baby It’s You,” the Shirelles would touch off the girl group explosion. Soon, the Crystals, the Ronettes, the Supremes and countless others would place the Shirelles in fierce and direct competition with their own devotees. The saturation would prove difficult to overcome, as would the catalyzing impact of the British Invasion on the rock and roll marketplace. With their fortunes declining, Owens and Coley departed in 1968. They were replaced by a pre-fame Dionne Warwick on a number of subsequent tours. However, the group was ultimately destroyed amid legal conflict with Scepter, which it turns out had largely screwed the young girls out of their royalties.

The Shirelles have reunited on occasion and each has also fronted its own incarnation of the group backed by hired hands. The Shirelles were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996.

70. Cliff Richard & the Shadows

Not necessarily a household name in the U.S., the Shadows would be the greatest hit-making machine of the rock and roll era in Great Britain. Beginning as a backing unit called the Drifters for Cliff Richard in 1958, Hank Marvin, Bruce Welch, and Brian Bennett supported the biggest and most successful of Britain’s skiffle acts. Following the threat of legal action from the increasingly famous American vocal combo also called The Drifters, the group became the Shadows.

Both on their own and under the Cliff Richard & the Shadows attribution, they were easily the most popular charting act in the United Kingdom before the emergence of the Beatles. Cliff Richard was already an established star by 1958, taking the influence of American predecessors like Little Richard and Elvis Presley to the #2 spot on the British charts with “Move It,” often regarded as the U.K.’s first original rock and roll hit. But with his scorching new support band, and particularly the influential work of guitarist Hank Marvin, Cliff Richard enjoyed enormous chart success.

As a unit, the Shadows also began posting singles, typically in the same surf, hot rod, and pop vein as America’s Ventures. On their own, the Shadows waxed the 1960 instrumental “Apache,” a fairly monumental recording and not just because it would spend five weeks at the top spot on the U.K. charts. “Apache,” would inform innumerable covers over the following years, eventually finding its way into the bloodstream of hip hop turntablism and becoming a cross-genre standard. The version by the Sugarhill Gang is still prone to filling dancefloors today.

Like many other ’45’-era bands, the Shadows would see a sharp downturn in single sales as the Long Player format hit its commercial stride in the mid-60s. But demand for the Shadows never truly waned, offering the band frequent opportunities to reunite with a wide variation of lineups from the 70s through to present day. Within the context of the British singles chart, only Elvis Presley outranks Cliff Richard & The Shadows. Still on the tour circuit today, Cliff Richard can claim more than 250 million records sold worldwide.

Photo By: Paul Hermans – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

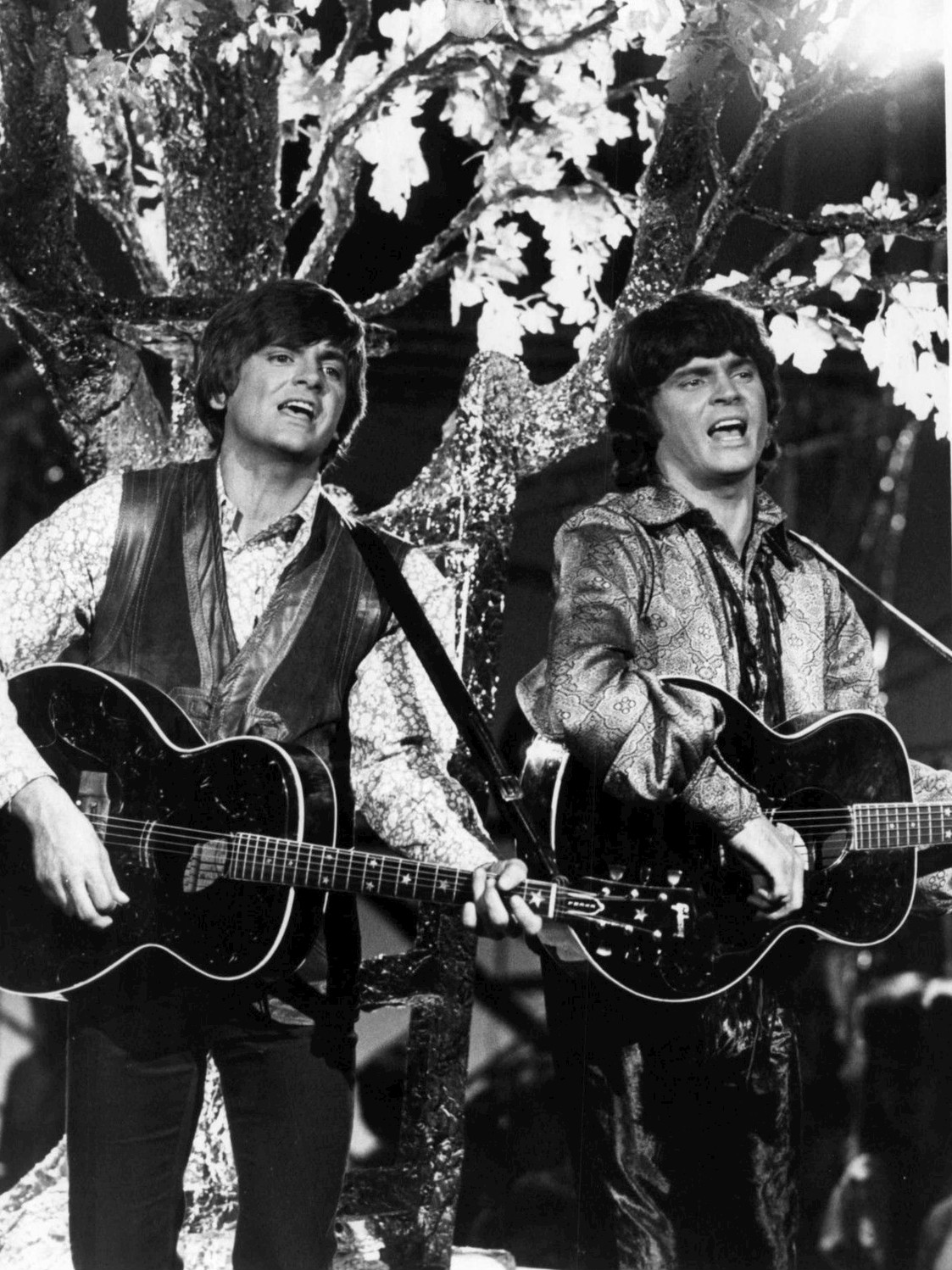

69. The Everly Brothers

Country music history is rife with famous brothers, though none ever had the crossover success enjoyed by the Everlys. Their mellifluous vocal harmonies and sonorous steel-guitar arrangements took brothers Don (nee 1937, Kentucky) and Phil (nee 1939, Chicago) from the country family-band circuit to global fame. Their contributions to popular music in their one decade of true prominence rank them among the forefathers of rock and roll.

The boys first gained prominence as part of The Everly Family, which included mother Margaret and father Ike. They were regularly featured on Ike’s Shenandoah, Iowa radio show in the mid 40s under the name Little Donnie and Baby Boy Phil. With the family’s relocation to Tennessee in the early 50s, the brothers completed their studies and lept headlong into the country music scene. Guitar-plucking virtuoso and RCA Victor studio manager Chet Atkins arranged their first auditions and connected them with a publishing deal, paving the way for a 1957 contract with Cadence.

Though their demo of the Felice and Boudleaux Bryant-penned “Bye Bye Love” had been rejected outright by no fewer than 30 labels, Cadence latched on and sold a million copies of the 45. Only Elvis Presley’s “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear” would keep the #2 hit from the top of the pops. Though the Everly Brothers were themselves accomplished and prolific songwriters, their partnership with the Bryant songwriting team would deliver them to their biggest hits and ensure their place in the pantheon of Golden Age rock and rollers. With “Wake Up Little Susie,” “All I Have To Do Is Dream,” and “Love Hurts,” the Everlys and the Bryants merged front porch harmonies with indelible and deliciously concise popcraft.

As the Everly Brothers became a constant and powerful presence on the country, pop, and R&B charts alike, they toured aggressively alongside other growing legends. Their 1957 and 1958 endeavors with Buddy Holly and the Crickets had a particularly profound and mutual impact on both acts. The brothers were both deeply affected by Holly’s tragic 1959 death.

The following year, the Everly’s moved to Warner Brothers and released “Cathy’s Clown,” a self-penned composition that led to their biggest hit. Though they would enjoy a handful of memorable charting entries during this time, the early 60s would also signal a sharp decline in their fortunes. A conflict with their publishing company disrupted their flow of royalties and their access to the Bryants. By 1961, both brothers had enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserves to avoid the active service draft. In the following years, though their influence came to loom rather largely in the work of artists like the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and Simon and Garfunkel, they themselves sold ever-fewer records.

Matters were worsened by Don’s substance abuse problems, particularly a troubling speed addiction that damaged his performance abilities. Over the next several decades, the brothers famously toured, feuded, fell out, reunited, and generally enjoyed an outpouring of appreciation and recognition from ensuing generations of critics, listeners, and musicians. Albums produced in the intervening years, both together and solo, largely emphasized the Brothers’ country roots. In spite of the tension and estrangement that marked their later years, the Everly Brothers were inducted as part of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s inaugural 1986 class. In 2001, they entered the Country Music Hall of Fame. Following a lifetime of brotherly dysfunction, Don was devastated when his younger brother passed away from lung cancer in January of 2014.

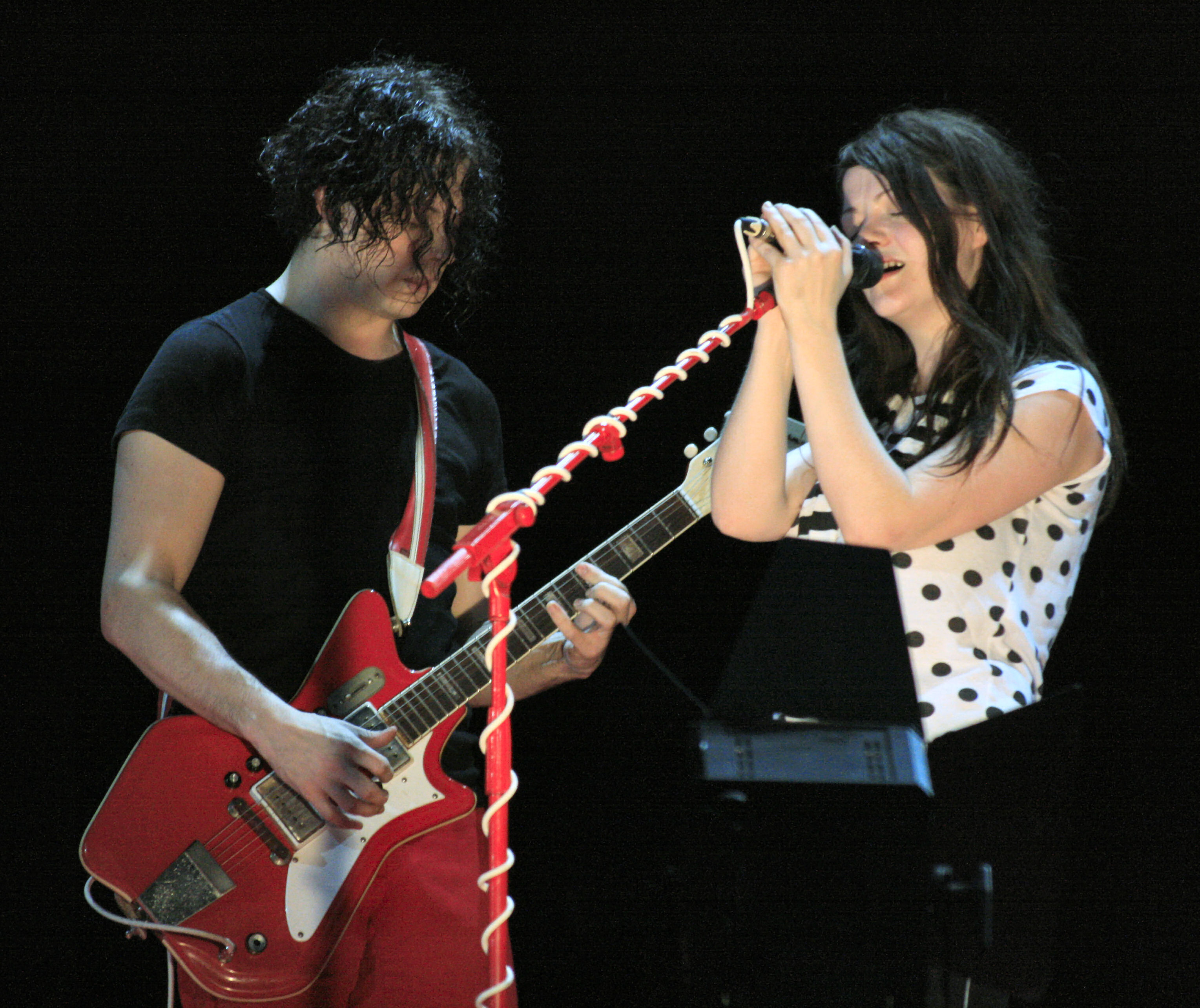

68. The White Stripes

It’s hard to believe that just two people could make such an unholy racket but The White Stripes were a powerhouse. The White Stripes began when a Detroit high school senior named Jack Gillis met Meg White, an employee at a restaurant where he occasionally read poetry. The two were married in 1996, with Jack making the unusual but professionally beneficial decision to take his wife’s surname. During their courtship and early marriage, Jack lent his potent guitar riffs to a number of Detroit garage groups, most notably Goober & the Peas.

As Jack built his reputation in an extremely active local scene, Meg White only picked up her drumsticks for the first time in 1997. Energized by her uninhibited and primitive style, Jack dispatched all other projects and formed the White Stripes. The White Stripes released their self-titled and self-produced debut in 1999, yielding a thunderous, post-Zeppelin commotion whose well-heeled loudness belied the fact that this band was a duo without a bassist.

The hyper-electrified blues and Jack’s cowpunk yowl were accompanied by an ingeniously crafted image. The musicians appeared super-serious and bedecked in only red, black, and white both on the cover of their debut and in any and all public appearances and photo shoots. Moreover, the Whites opted to keep their marriage a secret, instead proliferating the backstory that they were in fact brother and sister. The mythology proved rather persistent during the band’s initial run-up to success.

It would also prove beneficial when, even as the White Stripes gained steam through the typically ahead-of-the-curve British music press, the couple was quietly divorced in 2000. This would not prevent them from achieving a monumental breakthrough on their third record. 2001’s White Blood Cells became a hit in Britain during the summer of its initial release. As U.K. critics drooled over the group’s increasingly sumptuous hard rock, the U.S. finally caught on and embraced the Stripes as stars in 2002.

“Fell in Love With a Girl” earned the White Stripes heavy MTV rotation and a handful of video awards that year, helping the record achieve gold status. This would be all the more important an accomplishment when one considers the historical context. The late 90s and early 2000s had been a wasteland of boy-banders, teeny-boppers, and plop-rockers (the proper technical term for Creed and anything else which has been characterized as “post-grunge”). When the White Stripes broke through with pure, visceral, and affecting rock music, it helped to spark a minor garage revival. In addition to making space in the market for the Strokes, the Hives, and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the White Stripes inclined music collectors to reach back in history to rediscover influences like the Sonics and the Seeds.

On their fourth release and their major label debut (for V2 Records), Elephant (2003), the White Stripes enjoyed their greatest success. The iconic riffage on “Seven Nation Army” would not just grant the group its biggest hit. It would also provide future generations of marching band with a sporting arena standard right on par with Queen’s “We Will Rock You.” Critics loved Elephant, which became a #1 in the U.K. and a Top Ten record in the U.S.

The White Stripes would release an additional two albums, exploring a wider range of Americana, with divergences into hillbilly, country blues, and progressive metal. Critics and fans responded positively but touring and publicity had ultimately placed too great a strain on Meg’s personal life. In 2007, the White Stripes called it quits and their drummer largely returned to the private sphere.

Jack, by contrast, is among the most active and visible figures in the industry, working aggressively to keep rock and roll alive through his Willy Wonka-esque Third Man Records operation and his tireless work with the Raconteurs, the Dead Weather, and on his own acclaimed solo records. Evidence suggests that Jack White will remain among the most exciting and unpredictable musicians in the business for many years to come.

Photo By: Fabio Venni from London, UK; modified by anetode – White Stripes, CC BY-SA 2.0

67. A Tribe Called Quest

In its earliest stages of success, hip hop basically had two primary prerogatives: protesting and partying. Tunes were either designed to highlight the struggles of Black, urban Americans or to heal them by cutting loose on the dancefloor. A Tribe Called Quest ushered in a third steam, defined by a more thoughtful and less reactive discourse on the Black experience in America. Alongside artists like the Jungle Brothers and De La Soul, Tribe infused its fleet rhyming with laid back grooves, bebop jazz samples, and nuanced themes about race in America. As the most successful contingent of the Native Tongues Posse, Tribe offered a deeply optimistic, return-to-African-roots message that provided sunny relief to darker antecedents like Public Enemy and N.W.A.

Formed in 1985 around Q-Tip (MC), Phife Dawg (MC), and Ali Shaheed Muhammad (DJ) in Queens, Tribe’s distinctively non-danceable approach would take a few years to gain traction. Its debut, 1990’s >People’s Instinctive Travels did not garner immediate acclaim, despite containing no fewer than three of the group’s future classics in “Description of a Fool,” “Bonita Applebaum,” and most importantly, the Lou Reed-sampling “Can I Kick It?”

Though the concoction of chilled-out jazz licks and literary allusions gained quiet steam on college campuses, mainstream hip hop fans tuned out. But Tribe’s members gathered a steadily growing audience through collaborations with the slightly more popular De La Soul, not to mention by virtue of their own musical evolution. Tribe earned a reputation for digging out some of the rarest deep-cut samples in the game, providing the perfect texture for the increasingly dynamic lyrical flow between Phife Dawg and Q-Tip.

These qualities made 1991’s The Low End Theory something of a revelation. Driven by the bravura of lead single “Scenario,” Tribe established itself as the leading force in hip hop’s ascension to more positive lyrical imperatives. The Low End Theory earned gold certification and enjoyed almost total penetration of that year’s critical best-of lists.

Tribe remained in the warm and loving embrace of music critics with 1993’s Midnight Marauders, which earned a platinum certification and helped make all three of the group’s members sought-after collaborators among New School rappers.

They also embraced their position as thought-leaders within the Black community by decrying the violent East Coast/West Coast rivalry that dominated hip hop in the mid-90s, particularly on Beats, Rhymes and Life. The 1996 release reached the top spot on the charts.

Nonetheless, frustration with their label led Tribe to record just one more album before parting ways in 1998 to pursue varying solo careers. In 2006, Tribe would reunite for a brief tour, largely inclined by Phife Dawg’s mounting health problems and hospital bills. Sadly, those same health problems–complications related to diabetes–would claim Phife Dawg’s life in 2015, but not before the Tribe reassembled to record a secret record.

The surviving members would go on to release We Got It From Here…Thank You 4 Your Service the following year. Their first album in nearly a decade would debut at #1 on the charts, and more than likely, will stand as the iconic unit’s final achievement. Today, their collective output is widely held as one of the most important bodies of work in the hip hop canon.

66. The Pixies

When the Pixies sailed into the sunset in 1993, it felt a little bit like Michael Jordan retiring while everybody else was finally learning how to slam dunk. The quintessential alternative group, the perfect merging of pop sweetness and punk fury, grunge godfathers (and godmother), were all but gone by the time Nirvana ruled the world.

Formed in 1986 out of Boston, the Pixies were Kim Deal (bass), Joey Santiago (guitar), David Loverling (drums), and the group’s temperamental lead singer and songwriter, Charles Thompson (a.k.a. Frank Black/Black Francis). Though the band released only four records during its original run, it isn’t an exaggeration to suggest that this discography offers a complete road-map for grunge and alternative, from its punk ethos and its inherent hookiness to its template-setting loud-quiet-loud dynamic and obscure lyrics about mutilation and Satan.

To the point, if there is a Ground Zero for alternative rock, it’s probably the first pair of records produced by the Pixies. On Surfer Rosa (1988) and Doolittle (1989), Black’s high snarl, Kim Deal’s Riot Grrrl harmonies and Joey Santiago’s buzzing, surf leads resulted in a pair of albums so urgently ahead of the curve that you can’t believe they were made about the same time that Poison’s “Every Rose Has Its Thorn” was burning up the charts.

Just a few years hence, bands like Nirvana, the Smashing Pumpkins, PJ Harvey and Dinosaur, Jr. would go out of their way to admit they’d been ripping their moves from Surfer Rosa and Doolittle. Then, at the height of the alternative movement and at the point of their greatest success (they opened for U2 during a leg of their enormous 1992 U.S. Zoo TV tour), Frank Black informed his bandmates via fax that the Pixies were no more.

In their absence, and in the increasingly apparent wake of their influence, their legend grew, leading to a triumphant 2004 return to stage. The last 15 years have seen them crisscrossing the globe and headlining to audiences on a scale the band never imagined during its original run. They would also add two new studio albums to their discography with Indie Cindy (2014) and Head Carrier (2016). As a touring unit, largely fueled by their template-setting late-80s/early-90s output, they have reaffirmed all the reasons they are held in such high regard.

65. N.W.A.

N.W.A. was at once hip hop’s boldest and most confrontational group, forming in the ghetto of Compton and telling with visceral and explicit detail about life there within. Surrounded by violence, both at the hands of gangs and police officers, young Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, Eazy-E, DJ Yella, and Arabian Prince (replaced by MC Ren in 1988) took solace in one another. And beginning in 1986, they successfully set about to change the face of popular music.

N.W.A. provided rap music with some of the starkest, frankest, and most frightening street poetry ever recorded. With their 1988 debut, Straight Outta Compton, N.W.A. opened a window into Black life in L.A.’s toughest neighborhoods, authoring a lyrical exposé on a violent world in ways that had never before been outlined so bluntly, in music or elsewhere. So evocative was their message that their label, Ruthless Records, even earned itself a cautionary letter from the FBI.

N.W.A.’s run would be brief however, with internal disputes and royalty disagreements splintering the group even as its star was on the rise. In the face of censorship and FCC intervention, N.W.A. would eventually sell roughly 10 million records. But its greater importance would be realized in the careers of its two most important alumni.

Leaving in 1989, Ice Cube would embark on an immediately successful solo career, with classic records like 1990’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted and 1992’s The Predator making him a household name, so household in fact that he is as well-known now for his various film and television roles as for his part in forging gangsta rap.

By 1991, Dr. Dre had also departed N.W.A. to become the flagship artist at Death Row Records. His departure would lead to a public beef with Eazy-E who would himself enjoy short-lived solo success. (In 1995, Eazy and Dre would reconcile as the former lay on his deathbed, stricken with AIDS).

As for Dr. Dre, he would parlay his reputation from N.W.A. into 1992’s The Chronic, which stands today as a strong contender for the greatest hip hop record ever pressed. Smoothing out N.W.A.’s rough edges, Dre innovated a slow, drawling, groove-heavy production style fueled by Funkadelic and Ohio Players samples. He also introduced a shy, lanky stoner named Snoop Dogg, who instantly emerged as rap’s most charismatic young talent. With consequently inescapable MTV and radio smash hits “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang” and “Let Me Ride,” The Chronic went triple platinum, earned Dre a Grammy, and segued directly into Snoop’s massive ’93 debut, Doggystyle.

Over the course of the next decade, Dr. Dre had the midas touch, launching some of the most successful careers in rap history through discovery, musical collaboration, and production, including Tupac Shakur, Eminem, 50 Cent and, Kendrick Lamar. All this and Dr. Dre was ranked by Forbes in 2014 as the highest paid musician alive.

N.W.A. earns its place on this list as the launching pad not just for gangsta rap but for countless major milestones in the genre’s recent history.

64. The Drifters

What’s in a name? For the Drifters, pretty much everything. Don’t get me wrong. This doo wop ensemble is famous for its gorgeous harmonies, the immortal hits it produced in its first decade of existence, and the small handful of its former members who went on to become super famous in their own right. And yet, the name has served as a touring banner for well over 100 official vocalists and probably another hundred operating without full authorization to use the name.

The Drifters is a concept and one that continues to pull audiences even to date, though over time they’ve moved from marquee, to matinee, to early bird special. You can see these guys on the oldies circuit any time you want as long as you don’t care who exactly takes the stage. One reason for the group’s unusually high turnover was its original manager, George Treadwell. A jazz trumpeter and, for one decade, Sarah Vaughan’s husband, Treadwell owned the Drifters name and used it to contract several dozen musicians for notoriously low pay.

The first incarnation, formed in 1953, featured the yelping Clyde McPhatter, formerly of Billy Ward & the Dominoes, on lead. This incarnation produced the group’s first several classics, highlighted by the proto-rock and roll hit, “Money Honey.” McPhatter departed for a solo career in 1954 and enjoyed charting success, but reaped almost no financial rewards.

The period immediately following initiated the splintering of the Drifters trademark, with the original singers and Treadwell both separately employing the name. By 1958, Treadwell had established what remains the classic and definitive lineup of the group, featuring Charlie Thomas (tenor), Dock Green (baritone), Elsbeary Hobbs (bass), and emotive lead tenor Ben E. King. This is the lineup that would ultimately land in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, particularly for its output under the guidance of two distinct songwriting teams.

Famed Atlantic songwriters Leiber & Stoller, fresh off their success with the Coasters, landed the Drifters on the charts with “There Goes My Baby.” With Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, the combo produced soul classics like “Save the Last Dance for Me” and “This Magic Moment.”

Indeed, when King departed the Drifters over discontent with Treadwell’s meager compensation, he teamed up again with Leiber and Stoller to chart 1961 smash hits “Spanish Harlem” and “Stand By Me.” Next up for the Drifters was Rudy Lewis, who led the group on Leiber & Stoller’s “On Broadway“ as well as Goffin & King’s “Some Kind of Wonderful“ and “Up On the Roof.” When Lewis passed away in his sleep the night before a 1964 session, Johnny Moore woke up the next morning to lend his lead to “Under the Boardwalk.”

It was this same year that the Beatles landed in America and changed everything, including the fortunes and relevance of doo-wop acts like the Drifters. The hits dried up and the Drifters gradually faded from Atlantic before assuming their permanent place on the casino circuit.

Photo By: Atlantic Records – Billboard, page 1, 12 December 1964, Public Domain

63. Cream

Cream was short-lived and, if we’re being honest, some of its output dates about as well as shag carpeting. But the original power-trio is also rightly regarded as a leading exponent of hard rock in the late 60s. Jack Bruce (bass), Ginger Baker (drums), and Eric Clapton (guitar) formed what is often regarded as rock music’s first supergroup. All were seasoned veterans of the British blues scene, with Bruce and Baker emerging as members of the Graham Bond Organisation and Eric Clapton gaining his first glimpse of fame with the Yardbirds. Thereafter, Clapton and Bruce both graduated from the blues academy that was John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

Thus, by the time the three pooled their talents in 1966, their success was assumed. Indeed, the members themselves assumed it to the extent that they took their name to denote that they were the cream of the British music crop. On their debut, 1966’s Fresh Cream, the band merged jazz time signatures, blues compositions, and rock riffs, creating the heavy electrical stew that would be a touchstone for British psychedelic, metal, and progressive rock thereafter. Banging out the formula that would inform Led Zeppelin and The Jeff Beck Group in the not-too-distant future (each led by one of Clapton’s fellow Yardbird alums), Cream’s debut was half originals, half blues standards.

The album was a charting success on both sides of the Atlantic, leading to an American tour in early 1967. Though Clapton had already become an established star in England, this was his first blush of fame in the U.S. It was the release of Cream’s second record, 1967’s Disraeli Gears and its psychedelically-resplendent crimson cover, that propelled the trio to fame and set the mold for a boom of heavy British blues, not to mention offering a template for the next great power-trio, the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Disraeli Gears made compelling use of the wah-wah pedal and brimmed with big fuzzy guitars on tripped out tunes like “Strange Brew” and “Tales of Brave Ulysses.” With “Sunshine of Your Love,” Cream authored what may well be rock’s most quintessential electric riff this side of “Satisfaction.” The charting success of Disraeli Gears led to a summer tour in the U.S. that centered on an appearance at San Francisco’s Fillmore West. This tour was well-received and ultimately delivered Clapton to the fame that he has enjoyed since.

Cream was not always well-received by critics though, derided as they were for the sometimes pompous heaviousity that rooted their sound, a fact which secretly bothered Clapton. For their part, Bruce and Baker generally couldn’t stand to be in a room together, a personal discord which extended back to their days in the Graham Bond Organisation. Still, the band succeeded in producing the first double album ever to achieve platinum status with 1968’s Wheels of Fire. Half-studio, half-live, Wheels pointed in the direction of progressive rock with its denser instrumentation but remained steeped in the blues, as per Clapton’s game-changing extended jamming on Robert Johnson’s “Crossroads.”

But this supergroup’s longevity was never a real possibility. Its personalities were largely incompatible with one another and with the overall mission of the band. Clapton, in particular, was meant for far greener pastures and found himself particularly moved by the musical purity of the work his friends in The Band were doing with Bob Dylan in the natural splendor of upstate New York. He would eventually channel these feelings into work with Blind Faith and Derek and the Dominos.

Recording an album to be released following their demise, Cream split up in 1968, plated Goodbye in 1969, and entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993.

Jack Bruce went on to a colorful career as a solo artist and session man, passing away in 2014 at 71. Ginger Baker would pursue a fascinating post-Cream career, first as part of Blind Faith with Clapton, then as leader of Ginger Baker’s Air Force, and subsequently through a series of imaginative collaborations such as a 1971 performance with Afro Beat king Fela Kuti. Check out the 2012 documentary Beware of Mr. Baker if you want to learn more about this really scary dude who had been exiled from multiple countries prior to his passing in 2019. For those familiar with Baker’s prodigious appetite for excess, that he lived to see the age of 80 is nothing short of a miracle.

And of course, you know what became of Clapton.

62. Public Enemy

Public Enemy is the most overtly political act in hip hop history. Where groups like Run D.M.C. described urban Black life and N.W.A. raged against it, Public Enemy laid bare the sociological, economic, and political experiences of Black America. Where its contemporaries focused on everyday life in the ghettos, Public Enemy set its sights on the biggest targets: the media, the government, law enforcement, segregation, and the continuing effects of slavery. Setting these themes against a hard, stark musical backdrop, Public Enemy’s uncompromising confrontation has always demanded, and received, attention.

Forming in Long Island in 1986, Public Enemy centered around rapper Chuck D, MC Flava Flav, DJ Terminator X (since replaced by DJ Lord), and the Bomb Squad production crew. Fresh off the success of the Beastie Boys’ 1986 debut, Def Jam’s Rick Rubin sought a more explicitly political act. He found as much and more when he teamed up with Public Enemy to produce their debut record, Yo! Bum Rush the Show. The 1987 release gained a commercial bump from Public Enemy’s opening slot on the Beastie’s tour and achieved immediate critical praise.

The following year would see Public Enemy undertake a series of classic hip hop records deeply rooted in themes of Black pride and discontent. With It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988), Public Enemy unleashed a series of incisively observed and hard-to-refute assertions on “Don’t Believe the Hype” and “Bring the Noise.”

1990’s Fear of a Black Planet and its call to arms, “Fight the Power” may well mark the artistic peak of hip hop protest. Often identified as among the most important recordings to spring from hip hop’s Golden Age, it would sell one million copies in the U.S. in its first week alone. Today, it is included as part of the Library of Congress National Recording Registry. So too is Public Enemy included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Perhaps more than any artist of its genre, Public Enemy stimulated fearless and unrestrained dialogue on the experience of black Americans. The fact that the band succeeded in charting hits without ever straying from this intent suggests that its message came through loud and clear.

Photo By: Mika Väisänen, CC BY-SA 3.0

61. Big Brother and the Holding Company

Were it not for their lead singer, you’d never have heard of this band. For the most part, the members of this outfit were workaday Bay area rockers in the spirit of Country Joe & the Fish or Quicksilver Messenger Service. But their powerhouse lead singer elevates them from the status of psychedelic footnote to one of the subgenre’s key chapters. In Janis Joplin, Big Brother enjoyed the services of the era’s most captivating, distinctive, and heart-rending voice. Joplin’s bluesy wail and her inimitable presence remain affecting even today. For her many imitators, there have been none since her departure who can challenge Joplin’s raw power or emotional honesty.

Big Brother began its existence without its magnetic front-woman, forming in 1965 around guitarists Sam Andrew and James Gurley, bassist Peter Albin, and David Getz on drums. Alongside the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother established itself as a fixture in the burgeoning San Francisco scene. When they scored a gig as the house band at the Avalon Ballroom, they sought the services of a distinctive vocalist. They did nothing less than discover the most distinctive singer of the era, reaching out to Port Arthur, Texas native and Austin performer, Janis Joplin.

Joplin had been just then on the verge of joining fellow Texas tripsters, The 13th Floor Elevators when she was given the opportunity to front her own act. She joined Big Brother and the Holding Company in 1966 and they released their eponymous debut in the following year. Bluesy workouts like “Down To Me” were popular in the Bay Area and landed softly in the middle reaches of the Billboard charts. The album itself peaked at #60.

There was nothing soft, though, about the band’s appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival in June. At the height of the Summer of Love, Joplin absolutely floored audiences with a stunning display of vocal wattage. Monterey was a coming out party for the counterculture’s musical revolution and Joplin was quickly anointed as a key figure. Bedecked in feather boas, granny glasses, and second-hand dresses, she was as much a pioneer of hippie fashion as she was a leading voice for the movement.

On the strength of their newfound national recognition, Big Brother signed to Columbia Records and subsequently became the first band to play legendary promoter Bill Graham’s newly minted Fillmore East on March 8th, 1968. In August, they released Cheap Thrills, the band’s most fully realized and cohesive effort as well as a desert island recording of the psychedelic era. Janis Joplin is at her best and most lucid here, belting out Big Mama Thornton’s “Ball and Chain” and scoring a massive hit with her cover of Erma Franklin’s “Piece of My Heart.” (For trivia buffs out there, Erma Franklin was Aretha’s older sister).

Cheap Thrills spent eight non-consecutive weeks in the top spot on Billboard’s album charts and was certified gold. Its success cemented the mainstream penetration of the hippie subculture. It also made Janis Joplin a key figure there within, exposing her to all the praise and ridicule that this entailed. To both of these experiences, Joplin responded with increasingly excessive heroin and alcohol consumption.

Both in light of her singular fame and the desire for greater artistic versatility, Joplin departed Big Brother in late 1968, taking Sam Andrew with her. This left her old bandmates to wander pointlessly through two unspectacular albums before calling it quits. (Among others, a young Eddie Money unsuccessfully auditioned to fill Joplin’s vacancy.) In the summer of 1968, Joplin joined other luminaries of the era on the stage at Woodstock before releasing the occasionally satisfying but musically uneven I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama!

In early 1970, Joplin formed her own Full Tilt Boogie Band but also played several very well-received reunion shows with Big Brother and the Holding Company. Evidence suggested that both parties were at their finest when working together. Sadly, Joplin’s story is among the best-known tragedies of the era. Unable to reign in her own excesses, Joplin succumbed to a heroin overdose on October 4th, 1970. At the age of 27 (like Jim Morrison nine months later and Jimi Hendrix just two weeks prior), Joplin had been in the midst of her final recordings. The posthumously released Pearl (1971) yielded her biggest hit, the definitive take on Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee.”

Though Big Brother (which has continuously toured since 1987 in spite of the fact that all but two of its original members are now deceased) is rightfully seen as little more than the proving ground for Janis Joplin, this accomplishment alone justifies its inclusion here.

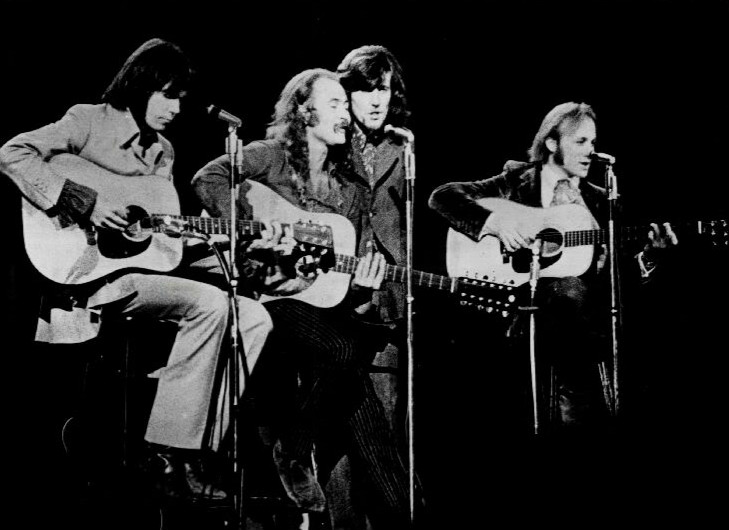

60. Eagles

Legend has it that the Eagles were a bunch of cynical jerks who didn’t much care for one another but who fully expected to earn a dumptruck of money for making music together. I don’t know them personally but a lot of the evidence kind of suggests that it’s true. If it is true, I guess you really have to tip your hat to them. The results don’t lie. With 200 million records sold worldwide, 100 of those in the U.S., the Eagles are the best-selling American band in our nation’s history.

It’s not just about the money though. To be fair, no matter how Jeffery Lebowski feels, the Eagles were responsible for some of the most evocative and symbolically relevant music of their decade. Many of their biggest hits still hold up and their album cuts go a little deeper than you might think. Like Crosby, Still, and Nash, the Eagles were originally formed by guys who had seen some success in the 60s. And like CSN, they helped shepherd popular music from its psych-mountain high into post-burnout country pastures.

The formation of the Eagles is essentially the story of the Southern California Laurel Canyon scene, and with it, the root history of the singer-songwriter era. In the late 60s, Jackson Browne, Glenn Frey, and J.D. Souther were just three aspiring musicians sharing a flat. When Souther’s girlfriend Linda Ronstadt needed a backing band for her third album, he recommended Frey. Frey, in turn, recruited drummer Don Henley from the band Shiloh. They added Randy Meisner of Ricky Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band and Bernie Leadon from the Flying Burrito Brothers and, after the recording sessions, immediately formed their own band.

Their veteran status earned them a contract in short order and they became a flagship artist for David Geffen’s fledgling Asylum Records. They took their name from a shared vision during a peyote trip in the desert but it also strikes one as a perfectly apt name for a band as distinctly American in its vision as were the Eagles. The lead single off of their self-titled 1972 debut, “Take It Easy,” was the product of a collaboration between Frey and his roommate Jackson Browne. It, and the album which contained it, were major charting successes.

In each of the following three years, the Eagles produced a series of records steeped in Southwestern mysticism, country outlaw imagery, lite-FM harmonies, and Nixonian bitterness. Though each of the Eagles’ full-length albums delivered the band increasing success, the band’s importance is perhaps better understood by way of its singles. Hits like “Witchy Woman,” “Tequila Sunrise,” and “Best Of My Love” became omnipresent on the singles charts and radio playlists, so much so that the albums containing them were far exceeded in sales by Their Greatest Hits (1971–1975).

In fairness, nearly everything is exceeded in sales by this 1976 compilation, which at the time of writing is the 6th best-selling album of all time. That same year, the Eagles released Hotel California. The addition of former James Gang gunslinger Joe Walsh signaled a move toward a harder rock sound and intensified the band’s growing draw as a stadium act. Propelled by the lyrical mystique and twin guitar dueling of its title track, Hotel California also emerged as one of the biggest selling albums of all time, having today moved more than 32 million copies.

The production of their final two albums saw the band splitting at the seams. Though they continued to produce charting radio hits, internal strife and exhaustion had begun to boil over. As backstage confrontations went from verbal to physical, the Eagles called it a day in the summer of 1980, their title as the defining act of the 1970s secured. The Eagles had come to perfectly reflect the burnout, bitterness, excess, egoism, acrimony, and Americanism of their decade.

When asked thereafter if the band might ever reunite, singer Don Henley had been reported to predict, “when Hell freezes over.” Hell indeed froze over when the Eagles reunited for a monumentally successful tour 14 years later, captured well on the 1994 live release Hell Freezes Over. The record reached #1 and reinforced the band’s reputation as an all-conquering commercial force. Their preordained induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame came in 1998.

Sadly, Glen Frey passed away in 2016, at age 67, due to complications from rheumatoid arthritis and pneumonia. Happily, Glen’s son Deacon Frey stepped into the breach, joining the band in 2018 along with solo country star (and one time Pure Prairie League vocalist) Vince Gill. Today, the Eagles remain a touring powerhouse, commanding stupidly high ticket prices.

59. Pearl Jam

More than any other band in circulation today, Pearl Jam is keeping the faith. Like the Rolling Stones before them, this good old rock band continues to churn, even as its contemporaries have long departed us. Emerging from the same time and place that gave us Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains, Pearl Jam is the lone survivor. Never as critically-acclaimed as Nirvana, nor as credible in the underground as Soundgarden, Pearl Jam is the sturdiest, most reliable, and longest-burning ember of the early-90s grunge fire.

Like much of this movement in its earliest stages, Pearl Jam’s story begins in the Great Northwest, where Seattle-based hard rockers Mother Love Bone were left reeling by the heroin overdose and death of lead singer Andrew Wood. Guitarist Stone Gossard and bassist Jeff Ament recruited guitarist Mike McCready and a San Diego gas station attendant named Eddie Vedder. Adding Dave Krusen (the first of five drummers), Pearl Jam was born at a Seattle cafe in the fall of 1990. Their debut with Epic Records, Ten was released the following year but only gathered steam slowly at first.

By the end of that year, however, Nirvana’s Nevermind had been unleashed upon the world. With it came an explosion of attention toward alternative music, grunge, and more specifically, pretty much anything that came from Seattle. Ten would be swept up in the current, becoming a landmark record during a landmark year. Pearl Jam was immediately different than many of the bands with which it was lumped. Its ethos seemed more metal than punk, even as it relied heavily on the same distorted minor chord progressions, loud-quiet-loud dynamic, and morbid themes that typified grunge.

Pearl Jam’s music possessed a more epic, arena-ready quality and earnestness not unlike that of U2. Vedder’s bellowing vocals anchored MTV groundbreakers like “Alive” and “Jeremy.” By 1992, Pearl Jam had become one of the biggest bands in the world. To date, Ten has moved roughly 13 million copies. Like Nirvana, Pearl Jam was pretty freaked out about the level of enormity it had attained in such short order. Their next two records, Vs. (1993) and Vitalogy (1994), centered around more acoustic balladry and experimental fancy, were intended to scale back the band’s audience.

They had the exact opposite effect, each debuting at #1 on the American charts and setting records in advance sales. What differentiated Pearl Jam most from its grunge contemporaries was its seemingly genuine and unconflicted sense of ethical propriety. By the time Cobain had taken his own life over the irreconcilable differences between fame and credibility, Pearl Jam had launched headlong into the good fight. Always a friend to the fan, Pearl Jam undertook a noble and quixotic battle with concert-promoting monopoly Ticketmaster in the mid-90s. Rebelling against the company’s outrageous service fees, Pearl Jam engaged in a two-year boycott of Ticketmaster venues, which was pretty much all venues.

The resulting lack of promotion and the distraction caused by its legal battles, which at one point did spark a Congressional investigation, substantially impeded the band’s album sales as the decade wore on. By the time they were forced to abandon their crusade, grunge was over and rock music had lost its 40 year hold on the Billboard charts to Hip Hop. But while their fellow flannel-rockers disbanded or overdosed, Pearl Jam settled into place as an unstoppable touring and recording act. Scaled to a core audience, a condition which one suspects the band might have always preferred, Pearl Jams still packs arenas and maintains the same unflinching integrity that has always been its greatest contribution to the world.

58. The New York Dolls

The New York Dolls did more, perhaps, than any other band to define the sound, the fashions, and the shambling recklessness that would become punk music. The chronological and musical bridge between the Stooges and the Ramones, the Dolls predated the use of the word punk but preemptively imbued it with its attitude and its Derelicte fashion sensibilities . The New York Dolls would only release two albums during their brief and chaotic existence, but these albums are a veritable blueprint for the genre that would swallow up New York and then London in just a few years.

Formed in 1971 around David Johansen (vocals), Johnny Thunders (guitar), Arthur Kane (bass), Sylvain Sylvain (guitar), and Jerry Nolan (drums), the Dolls were an immediately striking vision to behold. Tall imposing men bedecked in high heels, fishnet stockings, and garish makeup, the Dolls were as influential for their pioneering glam primping as they were for their raw, minimalist rock and roll.

Their two proper studio albums—New York Dolls (1973) and Too Much Too Soon (1974)—would sell poorly. Likewise, they were largely derided by less enlightened critics for their sloppy and slapdash attack. Still, the Dolls had become underground heroes to a set of disaffected street rats and junkies, most of whom would become regular performers at the CBGB in the years to follow.

Each of the Dolls’ live engagements was a spectacle of ragged intensity and wanton self-destruction. The Dolls would not survive as a unit to see just how wide their influence would spread. As it would through the entire scene, heroin permeated the band. Legend has it that the band’s 1975 breakup came about when Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan, unable to score while on tour in Florida, simply left the band and journeyed home to New York to meet up with their dealer.

It should come as little surprise that Johnny Thunders, Arthur Kane, and Jerry Nolan (as well as one-time drummer Billy Murcia) are all deceased by a combination of drug abuse and hard living. After a strange turn as dance floor huckster Buster Poindexter (who’s “Hot Hot Hot” is a conga line standard), David Johansen successfully reunited with Sylvain Sylvain and a few hired guns to reform the Dolls in 2004. They would even go on to release three new studio albums in the coming years before Sylvain Sylvain’s passing in 2021.

Today, the Dolls are granted the reverence befitting cult legends. Though their run was inevitably brief and their implosion assured, they blazed a brilliant path for the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, and even hair metalists like Motley Crue.

Photo By: AVRO – FTA001019054 011 con.png Beeld En Geluid Wiki – Gallerie: Toppop 1973, CC BY-SA 3.0 nl

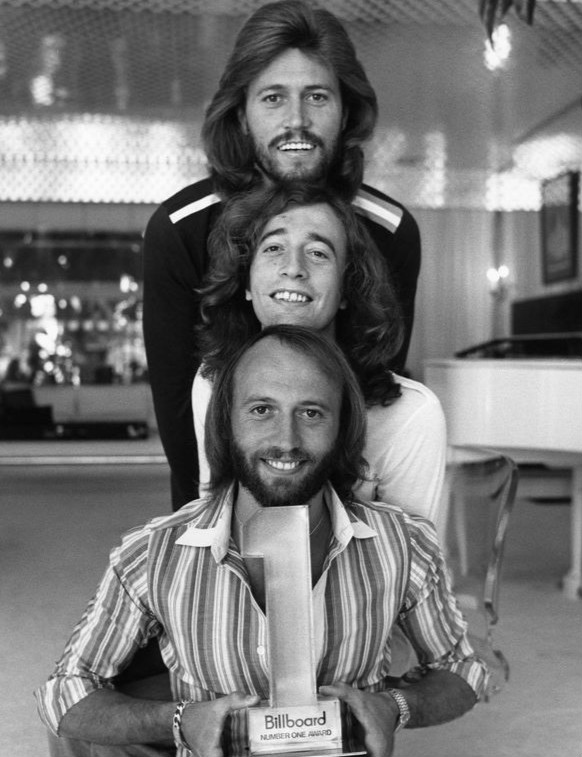

57. The Bee Gees

When he inducted the Bee Gees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997, Beach Boy Brian Wilson referred to the Brothers Gibb as “Britain’s first family of harmony.” It’s easy to disregard this band as a disco novelty act if you aren’t acquainted with the true scope of their accomplishments. But the reality is, particularly on a commercial scale, the Bee Gees are in the pantheon with Elvis, the Beatles, and Michael Jackson.

Though their greatest fame came at the tail end of the 1970s, eldest brother Barry and twins Robin and Maurice formed their trio all the way back in 1958 as teenagers in Manchester. After moving to Australia as a family in the early 60s, the brothers released a string of a dozen hits or so. Success, however, was hard-won in that first decade so the Bee Gees returned to England in 1967 and partnered with a new manager who, like every other manager of a British band from the era, assured audiences that his clients were the next Beatles. Given their talent with a melodic hook, their sweet harmonies, and the fact that nobody had the Internet at the time, the marketing ploy was generally successful. Radio listeners just assumed they were hearing new songs by the Beatles.

This allowed “New York Mining Disaster 1941” and “To Love Somebody” to ascend to the Top 20 on both the American and British charts. The latter is a pop standard that has been covered by Rod Stewart, the Animals, and Janis Joplin. It was also savagely butchered by Michael Bolton some years hence. Though comparisons to the Beatles persisted, much to the benefit of the rising trio, their three-part harmonies were something quite different, anchored distinctively by Robin’s soaring falsetto. Indeed, the Bee Gees experienced their own mania as they toured Europe with a satchel of British Invasion-styled pop gems.

The Bee Gees capped off three years of permanent residency on the charts with 1969’s Odessa, a double album with progressive rock leanings that is often cited by critics as the group’s finest full length effort. The next several years saw infighting and even Robin’s brief departure. The Bee Gees continued to record and perform prolifically but spent the better portion of the early 70s declining in popularity and struggling to redefine their sound. At the advice of their friend Eric Clapton, the Bee Gees relocated to Miami in 1975.

The move exposed them to the American soul and R&B flourishing around them, leading to a full-fledged immersion into a more dance-based sound. With the release of “Jive Talkin’,” the brothers earned a #1 and made themselves a leading force in the sound that would define nightlife in the coming years. By the following year, both disco and the Bee Gees were on the rise, but it was the 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, and its accompanying soundtrack, that made both into era-defining headliners.

Carried by three Bees Gees #1 hits and another two hits composed by the Gibb brothers for other artists, Saturday Night Fever moved 40 million copies, making it the 2nd highest selling film soundtrack to date. It remains the most important and definitive record of the disco genre, an album singularly evocative of its time, and a catalyst to the Bee Gees subsequent reign over both the genre and moment in history. Fever spent an insane 25 weeks at #1.

Understandably, nothing could top this accomplishment, a fact which subjected the brothers to a subsequent decade of solo projects and internal conflict. Miraculously, the Bee Gees once again returned to the album charts in 1987. More importantly, in the years since, the Bee Gees began to enjoy the hard-earned critical respect that had eluded them during disco’s decline.

With the death of Maurice in 2001 and the passing of Robin in 2012, (in addition to the drug-related 1988 death of teen idol and youngest brother Andy) Barry is the lone surviving member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame group. In spite of their limiting association with the disco era, the Bee Gees moved a remarkable 220 million units worldwide during their 45 year run.

Photo By: NBC Television – eBay itemphoto frontphoto back, Public Domain

56. Aerosmith

Ok. So these days Steven Tyler looks like a melted popsicle with hair. And, admittedly, this band has pressed forward perhaps just a bit too long for its own good. But some among us are simply not meant to age gracefully. Indeed, grace was never a goal for the Bad Boys From Boston. Aerosmith came to be in 1969, when a young Steven Tyler (nee Tallarico) took in a live performance by The Jam Band, featuring guitarist Joe Perry and bassist Tom Hamilton. Enthralled by their raw energy, Tyler befriended the musicians and, adding Joey Kramer (drums) and, shortly thereafter, Brad Whitford (rhythm guitar), formed the classic Aerosmith lineup that remains improbably intact today.

Signing to Columbia Records and releasing their self-titled debut in 1973, Aerosmith charted a minor hit with the Tyler-penned “Dream On,” arguably the prototypical hard rock power ballad. The next several years saw Aerosmith climb into national prominence on the strength of breakout records Get Your Wings (1974) and Toys in the Attic (1975). FM staples like “Sweet Emotion” and “Walk This Way” rocketed Aerosmith to the top tier in an era where hard rock bands were enjoying ever larger stages and ever gaudier album sales.

Speaking of gaudy, these guys raised the bar considerably. Borrowing liberally from the cross-dressing proto-punk pioneers The New York Dolls, Aerosmith perfected the hair metal glam look that would saturate MTV a decade hence. Tyler and Perry emerged both as the band’s songwriting braintrust and its visual centerpiece. The latter offered leather-bedecked minimalism as a stark contrast to Tyler’s flowing silk scarves and brightly colored spandex. Nicknamed the “Toxic Twins,” Tyler and Perry were the 70s antecedent to the previous decade’s Glimmer Twins, Mick and Keef.

By the late 70s, Aerosmith would be consumed by its trademark toxicity. Drugs, alcohol and excess permeated the band’s world. Aerosmith’s run of platinum success continued until 1978, when tension led to the departure of both Perry and Whitford. Over the next four years, with replacement members aboard, Tyler fronted a vastly inferior version of his band while, according to some accounts, wandering the streets of New York in search of heroin. Though the original members of the band came back together in 1984 under a contract with Geffen Records, it was not until their collective completion of drug rehab the following year that Mach II of Aersomith was truly underway.

By any standard, the band’s rebirth and its ascendance to even greater and more sustained success defies likelihood, as does the path that it took to get there. Who might have guessed that Aerosmith’s rebirth would coincide with a landmark moment in the evolution of hip hop? The erstwhile rockers collaborated with Old School pioneers Run D.M.C. to recast “Walk This Way” as both a groundbreaking rap record and video. It became the first hip hop song to break the Billboard Top five and the video remains a landmark of both the genre and the medium.

It would also begin a decade of dominance for Aerosmith. With its next four records, Aerosmith inserted itself as a permanent fixture on the charts. Permanent Vacation (1987), Pump (1989), Get a Grip (1993), and Nine Lives (1997) served as fuel for a steady stream of stadium tours and radio hits. The band’s early-90s success was buoyed by a trilogy of MTV videos featuring Liv Tyler and Alicia Silverstone (“Cryin’” “Amazing” “Crazy”), the popularity of which placed the middle-aged rock gods in the thick of a more youthful alternative boom.

All told, Aerosmith’s track record distinguishes it as one of the most successful American rock acts in history. With more than 150 million records moved worldwide, 18 million platinum albums and 25 gold records, Aerosmith is the most certified American band of all time. Add to that 21 Top 40 hits, nine of them reaching #1 on the Mainstream Rock chart, four Grammys, and 10 MTV music video awards, and these skinny-assed Rock and Roll Hall of Famers are true heavyweights of the genre.

Photo By: David W. Baker – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

55. The Beastie Boys

When they released a debut album brimming with frat-boy antics and party mixtape bangers, you could have been forgiven for dismissing the Beastie Boys as little more than a trio of sophomoric pranksters. If you still think that, you really haven’t been paying attention. Turns out that “Mike D” Diamond, Adam “MCA” Yauch, and Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz were the real deal.

Originally forming as a punk outfit called the Young Aborigines in the early 80s, the Beastie Boys officially adopted their mantle in 1981. They worked as a mid-level hardcore band, opening for acts like the Dead Kennedys and the Misfits and appearing at famous New York punk haunts like CBGB and Max’s Kansas City. In 1983, as rap emerged to greater prominence in the boroughs of New York, the Beastie Boys tried their hand with a novelty tune called “Cooky Puss,” which of course references the beloved Carvel Ice Cream cake character.

“Cooky Puss” proved a live favorite for the band, inclining the Beastie Boys not only to incorporate additional rap-rock hybrids into their set but to hire a DJ. They hooked up with NYU student Rick Rubin, who in addition to spinning for the band, agreed to produce their first record. He formed Def Jam Recordings around this intent, placing the Beastie Boys at an epochal event in the coming Golden Age of hip hop. Indeed, Rubin and his label would become defining forces in the genre.